Carl Shulman is a Research Associate at the Future of Humanity Institute. He recently appeared on Dwarkesh Patel’s podcast to discuss what he calls an “intelligence explosion.” I am an AI newbie. To better understand Shulman, I decided to reconstruct the former’s arguments as he presented them for Dwarkesh. I am ignoring the latter part of their discussion about alignment. Please note my prior knowledge of AI is limited. I am relying on Cunningham’s law to help me learn. Any misrepresentations of Shulman’s views are my responsibility and I welcome corrections.

Intelligence Explosion

Shulman’s core idea is AI could undergo rapid improvement fueled by — you guessed it — improvements in AI. Once AI has gotten sufficiently good, it can improve AI researcher productivity, which makes better AI. Capabilities then balloon in short order leading to an “intelligence explosion.” Shulman talks about AI abilities doubling every X years to doubling every X/2 years, to doubling every X/4 years, et cetera. If this sounds wild, remember there is historical precendent for a similar “explosion.” In 1975, Gordon Moore mused that the number of transistors on a computer chip would double every two years. He’s been proven roughly right, even to the current day. If we can double the capabilities of hardware at a constant rate, it’s plausible we could double the capabilities of software even quicker.

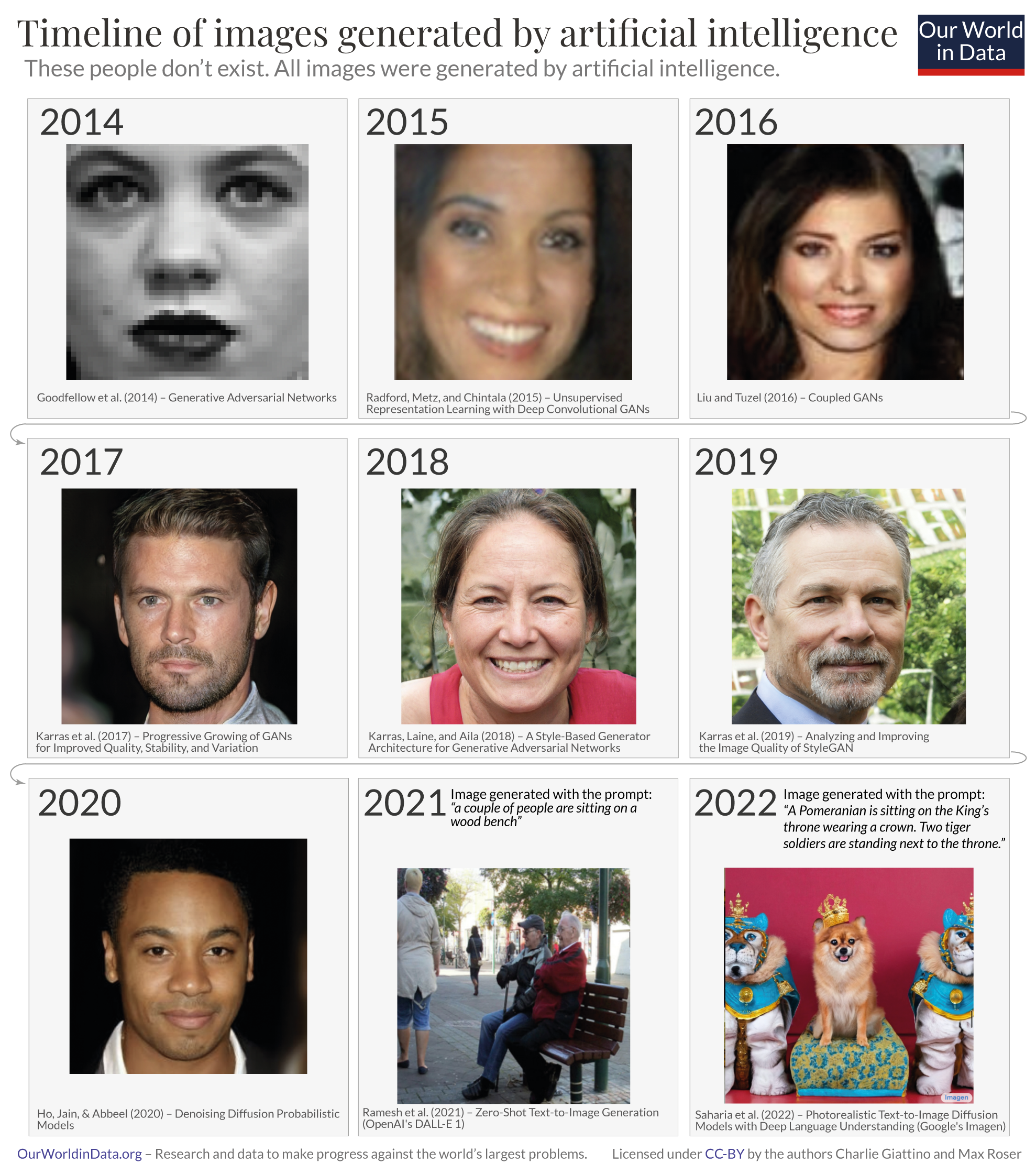

Experience seems to bear out an approximate “Moore’s law” of AI, too. I’m not familiar with the technical benchmarks researchers use to measure model performance, but progress has been quick even to the layperson. Our World in Data compiled nice graphics which put AI capabilities into context over time. The first details how AIs have performed on language and image tasks over the last 20 years. The second demonstrates how much better AIs have gotten at producing images since 2014.

Can we reason AI capabilities have been doubling every two years a lá Moore’s law from these graphics? Definitely not, but they’re suggestive. At the least, it’s undeniable AI has been progressing rapidly.

The obvious consequence of an intelligence explosion is we get AGI1 quicker than we think. A less obvious consequence, according to Shulman, is we get an analogous “robot explosion” (my term). Right now, AI’s controlling robots are good at basic physical tasks. Fine-motor control is, and in the early days of AGI, will be, a human advantage. The only way for AIs to improve will be to train off data collected from the robotic “bodies” they’ll inhabit.2 AIs, then, will persuade (coerce?) humans to produce more robots that will be needed to collect robot-specific data which can train AIs in physical tasks. With our fleshy hands and feet, we can do the things AIs find difficult, under the guidance of of highly intelligent AIs to maximize productivity. Shulman reasons that if we convert the current automobile industry to robot production, we can produce a billion human-size robots a year. Eventually, the AIs would have enough robot sensor data to do delicate tasks themselves. Once this happens, he says the robot population could be doubling in “months.”

Shulman does not think we’re necessarily on the brink of an intelligence explosion. He believes AI capabilities will grow quickly in the short term as more resources are redirected to AI from other fields. If AIs reach the point where they’ll accelerate AI research during the short-term quick growth, we’ll get an intelligence explosion soon. Alternatively, progress stalls, and an explosion is farther off.

Counterarguments to an intelligence explosion

You might be sceptical of an intelligence explosion. I see three main objections. You could doubt AI’s capability to accelerate AI progress in a meaningful way, you can argue there’s a resource constraint which prevents an explosion, or you could think the upper bound on AI ability is too low. Shulman addresses all three of these in his conversation with Dwarkesh. I’ll relay them in turn.

AIs cannot meaningfully contribute to AI progress

In a certain sense, this objection is clearly false. AI’s are already directly contributing to AI research. As is often noted, Github Copilot is used by employees at OpenAI, so GPT-3 already contributes to progress on other OpenAI models.3 What’s less clear is whether AIs can dramatically accelerate the rate of improvement. Shulman describes the best case scenario:

[AIs] boosting [humans’] effective productivity by 50 or 100%, and if you then go from like eight months doubling time for effective compute from software innovations, things like inventing the transformer or discovering chinchilla scaling and doing your training runs more optimally or creating flash attention. If you move that from 8 months to 4 months and then the next time you apply that it significantly increases the boost you’re getting from the AI. Now maybe instead of giving a 50% or 100% productivity boost it’s more like 200%. (18:38)

To get these productivity boosts, AIs need not be fancy. They can just automate some things but do them more quickly than any human.

Readers might be sceptical here. What exactly are these early AIs automating? Is automation alone enough to kickstart a rapid improvement feedback loop? Shulman’s response is “yes” and “yes.” In addition to automating the nasty parts of any job, including AI research, subhuman-level AIs can do concrete things to directly advance AI progress that a workforce of humans would never attempt. For instance,

[If] the AI can generate a lot of unit tests and then can try and produce programs that pass those unit tests, then the interpreter is providing a training signal and the AI can get good at figuring out what’s the kind of programming problem that is hard for AIs right now that will develop more of the skills that I need and then do them. You’re not going to have employees at Open AI write a billion programming problems, that’s just not gonna happen. But you are going to have AIs given the task of producing the enormous number of programming challenges.

Personally, I think the idea of AI increasing the rate of AI progress is quite strong. As mentioned, the basic case of low-level AIs functioning as a productivity tool for research is already happening. The more sophisticated case of AIs creating training data for themselves is also somewhat a reality. AlphaZero (a successor to AlphaGo) reached superhuman Go levels by playing against itself, or, in a sense, providing its own training data.

Resource constraints on an intelligence explosion

Even if AIs could accelerate their own improvement enough to cause a self-reinforcing feedback loop, there might not be enough resources in the world to support one. The “fuel,” so to speak, of AI improvement may be exhausted quickly. After that point, AI progress could be bottlenecked by these resources and not “explode.”

GPUs

GPUs are one candidate scarce resource. GPUs are superfast processors well-suited for computationally intensive tasks like rendering graphics, mining crypto, or training LLMs. My nontechnical impression is if GPUs did not exist, training GPT-3 level models would be nearly impossible. GPUs are also expensive, difficult to manufacture, and are currently subject to geopolitical risk. A single Nvidia H100 GPU currently costs ~$35,000, and OpenAI reportedly used more than 10,000 similar units to train GPT-3.4 A GPU fab takes 10 years to build, and the best ones are located in Taiwan, which China claims. Sceptics may reason any one of cost, manufacturing issues, or war could preclude a Shulman explosion.

I’ll start by reconstructing Shulman’s thoughts on manufacturing bottlenecks. Please note this section is approximate since I’m piecing together what he said at different points in the interview to create a reasonable view.

Shulman’s counter to manufacturing bottlenecks is enough improvements in software can compensate for any slowdowns in hardware. AIs run on sufficiently powerful GPUs can speed AI research and result in better AIs implemented on the same GPUs. Even if GPU progress halts, there is still room to improve AI on the software side by orders of magnitude, so Shulman’s reasoning goes.

Those [existing GPUs] if they were running AI software that was as efficient as humans, it is sample efficient, it doesn’t have any major weaknesses, so they can work four times as long, the 168 hour work week, they can have much more education than any human […]. So you combine the things tens of millions of GPUs, each GPU is doing the work of the very best humans in the world […] And so when you consider this — tens of millions of GPUs. Each is doing the work of 40, maybe more of these existing workers, is like going from a workforce of tens of thousands to hundreds of millions. You immediately make all kinds of discoveries, then you immediately develop all sorts of tremendous technologies. (18:38)5

The “tremendous technologies” in software can be immediately implemented on the existing GPUs.

Initially the returns are especially high in doing more software and the reason for that is again, if you improve the software you can update all of the GPUs that you have access to. Your cloud compute is suddenly more potent. If you design a new chip design, it’ll take a few months to produce the first ones and it doesn’t update all of your old chips. (1:34:37)

I’m not sure how far he’s willing to go, but the extreme version of Shulman’s point is we could have an intelligence explosion on the existing stock of millions of high-performance GPUs. Even if it takes 10 years to build a fab for new chips, AIs could still improve rapidly.

I’ll save discussion of GPU cost for the next section, since it’s best addressed by reasoning about money as a constraint to an intelligence explosion in general. To close, I’ll briefly touch on the risk conflict in Taiwan poses to AI. Dwarkesh Patel recently questioned Ilya Sutskever, Chief Scientist at OpenAI, about what a disaster in Taiwan would mean:

Dwarkesh Patel

How vulnerable is the whole AI ecosystem to something that might happen in Taiwan? So let’s say there’s a tsunami in Taiwan or something, what happens to AI in general?

Ilya Sutskever

It’s definitely going to be a significant setback. No one will be able to get more compute for a few years. But I expect compute will spring up. For example, I believe that Intel has fabs just like a few generations ago. So that means that if Intel wanted to they could produce something GPU-like from four years ago. But yeah, it’s not the best,

I’m actually not sure if my statement about Intel is correct, but I do know that there are fabs outside of Taiwan, they’re just not as good. But you can still use them and still go very far with them. It’s just cost, it’s just a setback.

Monetary constraints

GPT-4 cost more than $100 million to train. Bigger, better models will cost more, maybe by orders of magnitude. Dwarkesh Patel asked Shulman on whether we can kickstart an intelligence explosion before models get too expensive.

Even if we have greater effective compute from hardware increases and better models, it’s hard to imagine how we could sustain four or five orders of magnitude greater effective size than GPT-4 unless we’re dumping in trillions of dollars, the entire economies of big countries, into training the next version. The question is do we get something that can significantly help with AI progress before we run out of the sheer money and scale and compute that would require to train it? (28:26)

Shulman responds by emphasizing the potential payoffs of building powerful AI. If an AI costs $1 billion to develop, you need to expect at least $1 billion in gains to justify it. According to him, the math works out at the trillion-dollar scale.

From where we are right now seeing the results with GPT-4 and ChatGPT companies like Google and Microsoft are pretty convinced that this is very valuable. You have talk at Google and Microsoft that it’s a billion dollar matter to change market share in search by a percentage point so that can fund a lot. On the far end if you automate human labor we have a hundred trillion dollar economy and most of that economy is paid out in wages, between 50 and 70 trillion dollars per year. If you create AGI it’s going to automate all of that and keep increasing beyond that. So the value of the completed project Is very much worth throwing our whole economy into it, if you’re going to get the good version and not the catastrophic destruction of the human race or some other disastrous outcome.

[…] These large tech companies have R&D budgets of tens of billions of dollars and when you think about it in the relevant sense all the employees at Microsoft who are doing software engineering that’s contributing to creating software objects, it’s not weird to spend tens of billions of dollars on a product that would do so much. And I think that it’s becoming clearer that there is a market opportunity to fund [expensive models]. (29:37)

In general, Shulman probably sees money as another accelerant to an intelligence explosion, not a constraint. He often emphasizes how AI can make workers more productive or automate their work altogether, saving wage expenses. Since the payoffs are so big, companies should be willing to spend billions of dollars on AI research. The same incentives solve problems on the GPU side.

If in fact you’re getting very high revenue from the AI systems and you’re actually bottlenecked on the construction of these fabs then their price could skyrocket and that could lead to measures we’ve never seen before to expand and accelerate fab production. (35:09)

Technological limitations

An intelligence explosion may stall because AI can’t get much better. No matter the money and GPUs we toss at it, it could impossible to build hyperintelligent systems with our current knowledge (GPTs, neural nets, etc…), so the sceptic says. Of course, Shulman thinks otherwise. He uses examples from primate evolution to argue the difference between a hyperintelligent system and current, less intelligent ones is a matter of scale.

[Herculano-Houzel has a paper] discussing the human brain as a scaled up primate brain. Across a wide variety of animals, mammals in particular, there’s certain characteristic changes in the number of neurons and the size of different brain regions as things scale up. There’s a lot of structural similarity there and you can explain a lot of what is different about us with a brute force story which is that you expend resources on having a bigger brain, keeping it in good order, and giving it time to learn.

[…]

In my experience over the last 15 years the things that people call out are like —”Ah, but the AI can’t do that and it’s because of a fundamental limitation.” We’ve gone through a lot of them. There were Winograd schemas, catastrophic forgetting, quite a number and they have repeatedly gone away through scaling. (41:23)

Shulman also emphasizes the evolutionary pressures which prevent humans from achieving maximum intelligence aren’t present in developing AIs. Humans are much less intelligent than we could be. Having larger brains helps us navigate social environments and make tools, but brain size carries tradeoffs. We already devote, according to Shulman, 20% of our metabolic energy to our brains, and our evolutionary past didn’t always value intelligence. Having a robust immune system or “big muscles to throw spears” was often balanced against scaling our brains. Dwarkesh also points out human head size is limited by hip width. We were fortunate to have an evolutionary environment which rewarded human intelligence, but ours was far from ideal. AI evolution is not subject to the same constraints. Dwarkesh summarizes Shulman’s point nicely:

Okay. And the crucial point in relevance to AI is that the selective pressures against intelligence in other animals are not acting against these neural networks because they’re not going to get eaten by a predator if they spend too much time becoming more intelligent, we’re explicitly training them to become more intelligent. So we have good first principles reason to think that if it was scaling that made our minds this powerful and if the things that prevented other animals from scaling are not impinging on these neural networks, these things should just continue to become very smart. (52:06).

Commentary

I appreciated the conversation for emphasizing some factors which accelerate AI progress. Broadly, I’m comfortable with AIs already contributing to their own development, ignorant about GPUs as a constraint. However, I disagree with Shulman about the evolutionary environment current AIs are developed in and our willingness to train trillion-dollar models.

The evolutionary environment AIs face does not only reward intelligence. AIs we create must be smart, but also fast, personable, clear, scalable, and more, all in service of being profitable. They are not incentivized to be maximally intelligent. The largest models are developed by private companies who expect a return on their investment. In the same way human intelligence is impressive, but constrained by competing priorities like muscle mass and immune function, AIs will be intelligent, but limited by how profitable they are to their creators. A company with a choice between developing a hyperintelligent AI and a moneymaking one will choose the latter.

And I assure you, intelligence and commercial viability can diverge. Microsoft, OpenAI’s most largest patron, isn’t using AI to help mathematicians solve Millennium Problems. Instead, it’s building Business Chat, a ChatGPT-like product that has access to a company’s data. You can ask Business Chat about a certain customer, product, or conversation, and it can give you context since it ingests all of your information from Teams, Outlook, OneNote, Office 365, Windows, etc… It’s like having a tireless assistant who knows literally everything that’s happening in the company. For such an assistant to be useful, they only need to be highly informed and smart enough to speak in clear sentences. The most useful part of LLMs isn’t that they can do integrals, but that they’re a natural language interface to information. Perhaps private AI will be primarily developed to sell enterprise software rather than push the limits on intelligence.

For related reasons, I’m more sceptical of trillion-dollar models than Shulman. Although OpenAI is expecting revenues of hundreds of millions next year, could an LLM-type product return a trillion-dollar investment? Remember, a trillion dollars is a lot of dollars. To make a trillion, you’d have to sell a $1000 product to 1 billion people, or a $10,000 product to 100 million people. Shulman counters by saying advanced AIs could earn trillions by automating all the labor in the world. That’s far-fetched. Other countries would not be happy with a single (American) company stealing their citizens’ jobs. Italy already briefly banned ChatGPT for privacy reasons. Governments could do worse when their economies are at risk.

-

I honestly don’t know what AGI is. What does the “general” mean? That an AI is super powerful? That it is an agent? That it can improve itself? What do most people mean when they say AGI? ↩︎

-

This is why training robot AI is so difficult. You need to create thousands of robots to get enough data. Ilya Sutskever, Chief Scientist at OpenAI, actually made this point to Dwarkesh in a different podcast. ↩︎

-

I remember a paper from a while ago on how researchers used AI to find better matrix multiplication techniques, which improves AI. ↩︎

-

I don’t take this number too seriously. I’m not sure if OpenAI actually purchased these units or those were they units they touched in a Microsoft server farm. The H100 prices are likely higher than what OpenAI paid for them, too. However, 10000*$35000 = 350 million which is within an order of magnitude for how much it cost to train GPT-4. I’m ignoring (and ignorant of) a lot of things like the cost of hardware versus salaries versus the cost of running computations, but my point is GPUs are expensive and you need a lot. ↩︎

-

Shulman is addressing a different point in this quote, but I think the reasoning applies to concerns about GPU problems. ↩︎