Pick a skill you want to improve. It can be anything. Perhaps you’re keen on the oboe or want to graduate from paint-by-numbers to something more avant-garde. Or, you want to get in shape, learn new mathematics, or start a new career. Regardless, in a year’s time, you want to be substantially better at some thing than you are now.

You read internet blogs, so you’re compelled to model out your future progress. Suppose you are an oboe enthusiast and want to see how much you can expect to improve over a year. You decide to represent your oboe ability with a scalar. This is your “oboe score,” and it increases or decreases in tandem with your improving, or worsening, oboe skills. You decide your oboe score now is 1. As a result, increasing your score to 2 means you’re twice as skilled on the instrument than when you began to train. An oboe score of .8 means you’re 20% worse than when you started your regime.

Improving at the rate of 1% a day on the oboe sounds realistic to you. You’ve committed to daily practice, and the figure sounds modest. It is an approximation, though. Earlier in training, you can make larger percentage gains, and diminishing returns might strike later. However, you are also an oboe beginner, and so don’t expect to reach diminishing returns soon.

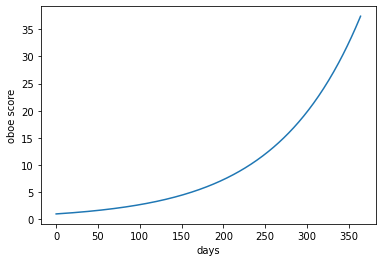

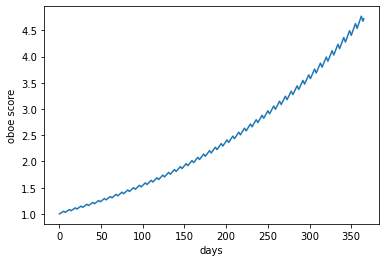

What happens, you wonder, if you improve 1% per day over the course of a year? What will your oboe score be then? Dash out a little code, and you get the following:

You’re shocked. The model claims daily 1% improvement can raise your oboe score to above 35 in a year (the final score is 37.4, to be exact). This is much more than you expected. Perhaps you were content with merely tripling or quadrupling your oboe score. The possibility of becoming 37 times better with modest daily improvements is a welcome surprise. A little confusion brews, however, on what exactly it means to be 37 times better. Is a Mozart concerto 37 times more difficult than Mary Had a Little Lamb? Is proper fingering 8 times as difficult as skating by on sloppy technique? You don’t know, ignore the issue for now. The difference between one oboist and another 37 times better should be clear and substantial.

Another thing puzzles you. If 1% daily improvements are sufficient to improve 37-fold, why haven’t you improved 37-fold at anything from last year to now? There are a couple explanations. Maybe every practice session does yield 1% improvement, but you don’t practice every day. Or, you practice every day, but you don’t get 1% improvement. For instance, we (hopefully) brush our teeth every day, but probably don’t improve with each session. We shouldn’t expect to be 37-times better this year than the last, then.

Or we have improved, but don’t notice it. You’d think it’s difficult to miss such dramatic improvement, but perhaps gains in oboe scores are not proportional to improvements in more traditional metrics. Suppose you’re trying to improve your 100m time. You start the same exercise as with the oboe, defining a “track score” that is currently 1. Your track score could double to 2, but that may not mean you’ve become twice as fast. More likely, you’ve dropped your time from 11 seconds to 10.8. In the track case, a 37-fold improvement in the track score could be the equivalent of going from 12 seconds to 10 seconds, not from 12 seconds to 12/37 = .32 seconds.

There’s something else striking about the model: returns take time. While the eventual improvement is 37-fold, it takes ~150 days to increase your oboe score to 5. Persistence, it appears, is key. In the beginning, progress will look nonexistent. Only after months will the bulk of improvement come. Stamina succeeds.

The continuous improvement model is nice, but crude. In actuality, people don’t practice every day. As a result, you cook up another model. You still begin with an oboe-score of 1, but have a certain probability of practicing on a given day. Call that practice probability “p.” When you practice, your oboe score still goes up by 1%. However, when you don’t, it decays by 1%. What happens at certain values of p? After all, you think, it’s almost unreasonable to practice every day. Life gets in the way, sometimes. Surely, you don’t sacrifice massive gains by resting occasionally.

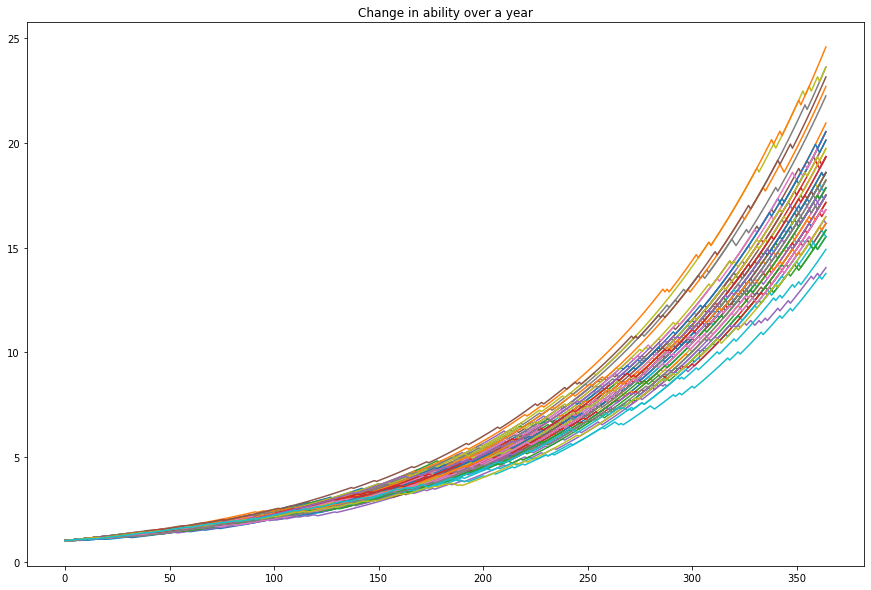

You dash out code for the second time and get the following:

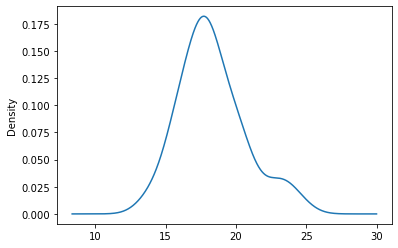

You ran 60 simulations where, on any given day, the probability of practicing is .9 while the chance of shirking is .1. The graph plots the results. There’s clear variation in the outcomes. The worst-performing future you only increased her oboe score to ~14. The best-performing one reached 25. The mean oboe-score across the 60 simulations was 18.3, with the following distribution:

Again, you’re surprised. Practicing 9/10 days is a lot. Still, on average, this equates to giving up almost half the gains you could have accrued from practicing every day. If you’re 90% as conscientious as the daily oboist, you might only be ~50% as skilled after a year.

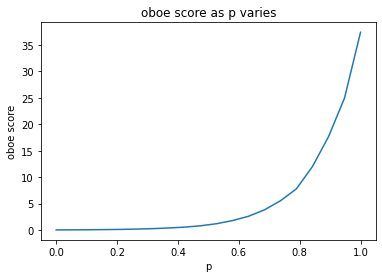

A parameter sweep demonstrates how quickly returns decrease as p does. You write code that takes a value of p between 0 and 1, simulates 60 runs with probability p of practicing on a given day, and then averages the various oboe scores at the end of the year. You end up with a graph that plots average year-end oboe scores as a function of p.

The cliff is steep. As mentioned, practicing 9/10 days on average kills almost half the gains, and practicing 8/10 days on average reduces your oboe-score to less than 10.

This observation prompts an uncomfortable thought. How much are you losing to the weekends? If the consequences of slacking 2/10 days are so severe, what happens if you fail to practice 2 consecutive days every 5? With trembling fingers, you write the code.

The curve looks nice, though slightly jagged, until you see where it ends. Taking weekends off, your oboe score would be 4.71, or only ~12% of what it could be with daily practice. Two days off does not sound significant, but they crater your oboe score. Daily effort, ostensibly, is worth nearly 10 times more than weekday effort.

Of course, there are problems with these models. Gains and losses could be best thought of in absolute quantities, not percentage terms. Skill development is also different than eking out 1% gains daily. We make massive strides as we learn the basics, and then our rate of improvement drops significantly. At the highest levels, a practice session might yield percent gains much smaller than 1%. John Isner likely doesn’t hit serves for an hour to improve. The practice is more so to prevent decay. More fundamental issues also lurk. It’s not clear what becoming “1% better” on the oboe, or a “1% better” taxidermist means. Most skills are difficult to measure, and there’s the issue of converting between the contrived scores used for the model and more established metrics. I’m even receptive to a reductio ad absurdum where you claim 1% improvements are unachievable, since they would imply you could get 37 times better by the end of the year with daily practice. Nobody, the line of reasoning goes, can improve by that much in such short order.

But the models tell us something frightening. Consistency is important. Daily practice can make us excellent, near-daily practice makes us good, and weekday improvements make us mediocre. This is scary because our opportunity costs have skyrocketed. Skipping one day of practice foregoes months of compounded growth. God wasn’t thinking about self-improvement when he created a day of rest.

Opponents of daily practice may believe they can hide in a “lumpy” theory of growth. They claim consistency is overrated because returns are concentrated in a couple instances rather than spread over time. Slaving for a certain 1% gain today is foolish since progress comes from the couple days with 20% returns. Painting tomorrow for two hours when we don’t feel like it is unwise. The majority of output stems from a couple inspired sessions. Better to wait until inspiration strikes and then hit the canvas.

The error here is ignoring the power of compound growth. The chance of a dies mirabilis is a deceptive voice telling us we’re ahead when we’re behind.