This trip was something of a trial by fire. Two years ago, I was itching for international travel and felt ready for it. I wanted it just as bad now, but was less ready. Living through a pandemic worked a change in my psychology. I now crave stability and predictability more than I am willing to admit, and interacting with others has been more difficult than ever. Traveling is not kind to either of these traits, and I learned that the hard way.

Fortunately, travel (even to France — another affluent western country) stresses you in all the best ways. You see new things and interact with people. You learn what it’s like to be utterly incompetent in a new culture. It’s like the antidote to Zoom University; Without a doubt, this trip made me less neurotic.

What follows are notes on travel and Paris. If I make generalizations, the usual caveats apply. It’s possible I’ve inferred too much from few observations, misread a situation, or am just plain wrong somehow. Don’t hesitate to let me know. If these read like the thoughts of a naïve monoglot American who has never left the country, it’s because they are.

And a big thanks goes out to Kelsey for suggesting the trip and taking me with her. I learned so much and had a wonderful time exploring a new city. COVID can try its best, but I had an unforgettable time.

(I recommend An Amish city, Department Stores, and Historical trajectory if nothing else)

The commerce of travel

I was shocked before I even left the States. At least at LAX, as soon as you clear security, the international terminal turns into a luxury mall. Dinky convenience shops that sell self-help books and trail mix are replaced by designer storefronts. Dior sunglasses, Gucci belts, and Hermés bags are only steps from your gate. You can buy designer makeup, high-end vodka, and cigarettes by the carton. There are LED screens three stories tall flashing chiseled European men wearing gigantic watches. It was the avionic equivalent of walking into a bus station and finding an Apple store.

I realize there are good reasons to sell expensive things in international terminals. They’re often tax-free zones, and international travelers are, I suspect, wealthier than domestic ones. There might also be a desire to wow foreigners. A luxury mall in an airport terminal signals “we’re a wealthy nation!”

Other language-lives

Hearing foreign languages in the US is nothing special to me. Hearing foreign languages in the Zurich airport was downright jarring. I had never internalized that people lived full, rich, lives in languages other than English. It was incredibly strange to me that the young girl on the plane who was talking with her mother in German has probably never had an English thought. Perhaps she never will. If so, nothing she ever (linguistically) thinks will be intelligible to me.1

I think I find this so strange because these people are closed systems to me. Their thoughts are in German, their interpersonal relationships are in German, and the most important things they read or hear will be in German. Their world is inaccessible to me, and in the short term, there’s nothing I can do to understand it.

Hearing foreign languages in the United States isn’t as jarring because the speakers probably know English. Their systems aren’t closed because, in principle, they can translate phrases or explain themselves.

Smoking

Smoking is more popular in Europe than America. Get close enough to anybody, and they probably smell like cigarettes. My girlfriend told me about a dinner she had in Barcelona where a woman eating alone near here played on her phone and chain-smoked for two hours while she ate. The Zurich airport has colorful, hip smoking lounges sponsored by cigarette companies where you can light up between flights.

This is surprising, considering I always associated poor health decisions with Americans. It’s nice to know we understood the health effects of cigarettes relatively early and changed our culture accordingly. It shows up in the data, too. Estimates suggest 20% of Americans over 15 smoke. In France and Germany, the same figures are 33% and 25%, respectively. The only European countries that have us beat are the Scandinavians, with Sweden, Norway, and Denmark boasting smoking rates of around 16-17%.

Cultural discomfort

When I traveled, I was very aware I was stepping into something called a “culture” with norms and expectations. If you violate them, you can receive social censure. If you conform, you can “blend in” and build rapport. Now here’s the catch: you have little idea what those rules are. Things are happening — often in different languages — and you don’t know what behavior is rule-following and what is idiosyncratic.

Not knowing the rules of the game was the most uncomfortable part of the trip for me. It was like staying in a stranger’s home where the only guidance they provided on how on to care for the house is in another language they think I speak. The best you can do is try and imitate the others staying in the house with you.

Thankfully, people can assimilate. I did, to some degree, and the discomfort faded. Still, it’s difficult to overstate how nice and familiar the U.S. felt after coming back. Being on home turf resolves all the cultural ambiguities which nag you while abroad.

An Amish city

The Amish seem to have decided 19th century technology was optimal. Parisians made a similar judgement about architecture. I got the impression every building in central Paris was either Medieval (Louvre, Notre-Dame, Saint Chapelle), a 19th century public work (Arc de Triumph, Palais Garnier), a Haussman building, or an unspecified type of “old.” Take this Google street-view of a residential street near my hotel.

We have a Haussman type building on the right, and an unspecified “old” on the left. The street-level shops can be quite modern, however. Here’s another example:

The left and right buildings are Haussman-type. The ones straight ahead are generally old.

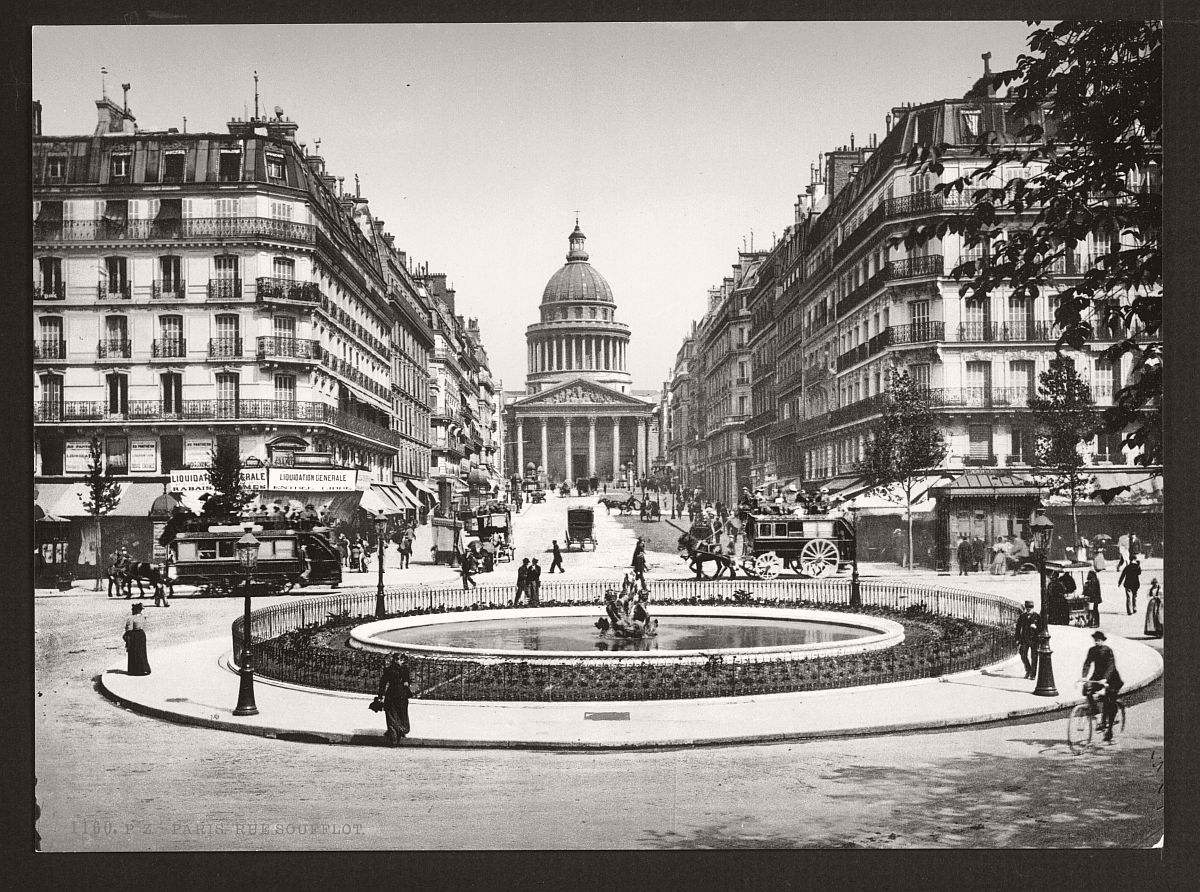

Blocks after block of Paris is like this. A pedestrian walking around the central city today sees roughly the same buildings as she would have in 1895. Here is a photo taken from Rue Soufflot from between 1890 and 1900, and one from approximately the same location with Google street view in 2021. Notice how the buildings on either side of the street have barely changed in 120 years.2

The aesthetics of Paris gives me mixed feelings. The city itself is gorgeous, and architectural continuity provides a valuable connection to the past. It’s difficult enough to understand what life was like back then, so being able to literally see the same things as them is helpful. But the only reason the past is still accessible to us is because the future never came. Most cities are characterized by high-rises and glass facades. Paris has few of either. Everything is cream limestone and cast-iron.3

Dress

Parisians dress well. I was somewhat embarrassed walking around in jeans. I never once saw someone in sweatpants.

Who’s valued

I’m deeply impressed with how France honors their intellectuals and artists. At least in Paris, it seems like they’re given a higher standing than popular entertainers.

For instance, I made a point of listening to a lot of French pop music prior to my trip. From my understanding, the pop superstars of the Francophone world include Angele, Lomepal, and Romeo Elvis. (There’s also a French rap/trap scene, but I didn’t listen to them much). Based on their popularity, I would have expected billboards, advertisements, or at least some indication of them in Paris. Imagine something like this:

Instead I got this:

(an advertisement for a French author’s memoir)

And dozens of ads for a Marcel Proust (Proust!) exhibit that I (regrettably) didn’t take photos of. I didn’t find a single reference to a French pop star during my stay.

There are gestures to French intellectuals almost everywhere if you look hard enough. For instance, the Eiffel Tower is inscribed with the names of 72 French scientists, engineers, and mathematicians. Eiffel wanted to present the tower as a scientific asset in an effort to preserve it, so he tried to associate it with France’s STEM legacy. Apparently, it worked. The tower still stands 113 years after it was scheduled to be disassembled.

There are more examples. The Pantheon contains a crypt housing some of the great men and women of France. Of course, it’s filled with generals and statesmen, but there are also philosophers, authors, mathematicians, and scientists. The first two graves you see on entering are Voltaire’s and Rousseau’s.

Later on, you can see Alexandre Dumas and Victor Hugo. There’s also Lagrange, Carnot (of thermodynamic fame) and Marie and Pierre Curie. The Curie’s graves were the most exciting for me.

To get a sense of how ridiculous this is, imagine if something like the Pantheon existed in the United States. Suppose Grover Cleveland, Alexander Hamilton, and Eisenhower were all buried underneath the Washington Monument next to John Steinbeck, the Wright Brothers, and Richard Feynman!

Public safety and homelessness

I dramatically underestimated how safe large cities could be. Of course, every city has bad parts, but I was pleasantly surprised how comfortable I was walking at night in a new city whose language I do not speak. I admit I am easily impressed, since I’ve only ever lived in Portland and Los Angeles. Now I know those cities (American cities?) are closer to exceptions rather than the rule.

There were also few homeless people. The ones I did see also looked relatively clean and sane. I’m unsure how much of this to attribute to the climate, government policies, or the relative lack of meth/opioid abuse in Europe.

Department Stores

This was the most shocking part of my trip. Parisians take their malls very seriously. I visited the Pantheon, the Louvre, Sacre-Coeur, Sainte-Chapelle, and Versailles, but the interior of Galeries Lafayette (a department store) made the largest impression on me.

Here’s what I’m talking about:

And this is a video I took while I was there.

My jaw dropped. When you visit a church or a palace, you expect it to overwhelm you. The builders are trying to communicate the awesome power of God or the Sun King. Sometimes they succeed and you leave a little more religious or afraid of Louis XIV. I had no such defenses or expectations for Galeries Lafayette, so it bowled me over.

There is also something strange about appropriating architecture associated with palaces and religious buildings for department stores. The message gets muddled. Gods and monarchs are trying to reduce you to a mote so you can internalize their divinity. If malls are going for the same effect, whose divinity are we trying to recognize? The owner of the mall? Commerce? CaPitAliSm? Our ability to purchase expensive things in beautiful places? Drilling down on this question makes the aesthetics seem empty. I know Galeries Lafayette is beautiful in some sense of the word, but I’m unsure what it’s trying to say beyond exclaiming “we’re rich!” And I don’t want to accept the simple signaling explanation because the architecture is almost too nice for that. I think there should be something more, but maybe there isn’t.

Can we use department stores as a model to explain why the stereotypical urban French are so angsty and existential? You have what used to be a highly religious country that is now largely secular. Nearly everywhere you turn in Paris there are churches, basilicas, and chapels all for the glory of God. The architecture is unambiguously beautiful, but you, as a French atheist, can’t get behind the message. You still want to build beautiful things, so you’re reduced to reusing grand columns and domes in malls. It looks nice, but part of what contributed to the religious architecture was an underlying sense of the divine. There is nothing divine about a department store, so you’re left with all the signifiers of beauty without any substance. This leaves you walking around Paris with a pit in your stomach because the churches are beautiful, but commit what you believe are profound philosophical mistakes, and you’re unable to replicate the architecture with the same grandeur because you’re unwilling to give a theological grounding to your buildings, even if they use the same motifs. You end up pissed at new buildings because they seem cold and empty, but paradoxically you’re the most satisfied with churches since they were brave enough to make divine claims.

Another note on Parisian department stores. I was pleasantly surprised many of them (including Galeries Lafayette) have a well-stocked bookstore on the top floor. Among the regular assortment of books, most have a gigantic section on French literature, a smaller section on psychoanalysis, and many beautiful coffee table books. Parisians are very into coffee table books. 4

The books can get high-brow, too. When I was there, Michel Houellebecq had a new novel out. Houellebecq, to my understanding, writes very serious fiction with serious themes, and is not for the faint of heart. He’s also known for calling Islam “the stupidest religion” and being tried by the government for inciting racial hatred. (He was acquitted).

But his novels occupied the most prominent shelves on the bookstore. There were stacks of copies everywhere. No other author occupied a more visible position in the multiple French-language bookstores I visited. Keep in mind this was also true of the department store bookstores (including Galeries Lafayette). This is the equivalent of your local Neiman Marcus stocking high-brown fiction in a prominent place and not getting cancelled because one of the authors insulted Muslims.5

Café behavior

Paris is littered with Cafés. They have tables two rows deep on the sidewalks where people sit, chat, drink, and have a cigarette. I never saw anybody on their computer in a café. Ever. In America, café’s and coffee shops are basically second offices. Perhaps everyone in Paris goes somewhere else to do their work, but I suspect I would get dirty looks if I brought a computer to a café.

What Paris whispers in your ear

“You should consume more high culture”

Historical trajectory

Imagine you’re an attendee at the world’s fair in 1890. Parisians have constructed the Eiffel tower, then the world’s tallest man-made structure by a large margin, for the occasion. There is also the Gallery of Machines, a building more than 250,000 square feet large, housing the latest in science and technology. Thomas Edison is here, as is a booth devoted to his inventions. You realize you’re also in a country with a rich history of science and technology. Lavoisier discovered oxygen, Amperé was a pioneer in the study of electricity, and Foucault showed the world the rotation of the earth. In case you like math, France also boasted Lagrange, Laplace, Borda, Galois, Cauchy, and Fourier. Leibniz also discovered/invented calculus in Paris.

It would be reasonable to believe France continues to be a world leader in STEM. In two decades time, the Curies would vindicate you. It makes sense, you think, that the country/city that birthed the enlightenment would be a beacon in science and engineering.

However, an observer in 2022 is left wondering what the hell happened. Can we imagine Paris erecting the world’s largest building today? What about building a structure the size of Galeries Lafayette dedicated to the latest in industrial technology? Didn’t Pasteur’s own institute abandon an attempt at a COVID vaccine? I think our 19th century observer would be confused that France’s primary cultural exports are art, humanities, fashion, and cuisine, rather than atomic physics and biotechnology.

A huge caveat to this is France’s performance in mathematics. As Nintil remarks, France has almost as many Fields Medal recipients — the Fields medal is the Nobel Prize of math — as the United States, even though it has roughly 10% of the U.S.’s population. The proportion of French students specializing in math is also 3x higher than the proportion in the U.S.

This seems puzzling, given my claims about the rest of France’s STEM performance. I think said claims are still valid, especially given France doesn’t have even close to similar prominence in other scientific awards (Nobel, Von Hippel, Draper, Turing). A potential explanation may have to do with France’s tight connection with the humanities and how we can think of math as a weird sort of humanity.

Identity and ethnicity

I’ve never thought much about my ethnicity. Some will chalk this up to “privilege.” I tend to think it’s because I grew up in Portland which has a “whitewashing” effect, and I’m mixed, so it’s more difficult to identify strongly with either of my halves.

Being in Europe made me think about my ethnicity. To my understanding, some people in Europe are living in the exact same place as their ancestors. This can give an ethnic basis for some aspects of national identity. Though France is committed to universalism, some aspect of Frenchness might be wrapped up in having Gallic ancestors. Likewise, some aspect of Catalanness could be associated with tracing your lineage to a specific tribe. What made an ancient Theben a Theben is that their ancestor sprouted from a dragon’s tooth. Genealogy determining identity is a familiar idea.

This made me realize, to some extent, I probably never could be “Vietnamese,” “Italian,” or “Indian.” My ancestors maybe never even heard of those places. As much as I adopt the language and culture, for as long as I live there, “true Italian-ness” (whatever that means) is unreachable for me.

Being mixed adds another dimension to that. Even if I were to try to live where my ancestors came from, becoming a “true X” still might not work. On account of being of two quite different ethnicities, I will look very different from the average Xer no matter where I go. There is no place on earth where I can find a community of individuals that look like me.

And I’m ok with that. I don’t feel a need to be a “true X,” “true Y,” or whatever. The entire experience, though, makes me much more thankful for America. At least in theory, there are no ethnic barriers to being an American. Or if there are (regrettable) “informal” barriers, they’re probably much less palpable than the barriers in Papua New Guinea, Siberia, or Ethiopia, or anywhere else in world (except plausibly Canada).

Footnotes

Thank you to Andy Trattner for doing some free copyediting

-

There are also philosophy of language/mind questions here. If I think “let’s go to the park” and someone in Jakarta thinks “Ayo pergi ke taman,” are we thinking the same thought? If so, how does that work? Would we have to say the two propositions have the same thought-referant, or pick out the same thought? What sort of thing would that be? If not, why? Does it have to do with the internal monologues of the two people being different? Or how the brain activity when thinking Indonesian sentences is different from the activity when thinking English ones? ↩︎

-

If you’re still not convinced of Paris’ age, look at this map. It color codes all of its buildings by construction date. Roughly a third of Parisian buildings were built prior to 1800. The plurality were built between 1851 and 1914. ↩︎

-

La Defense is very modern and technically in Paris, but is it really? It’s almost treated as a separate city rather than part of Paris proper. ↩︎

-

The covers of regular books in French bookstores are also superb. Even for English-language books, they manage to sell the editions with the best-looking covers. ↩︎

-

And the department store bookstores get more high-brow. Some also sell books from the Pleiades Library, which produces beautiful leather-bound volumes of works by primarily French authors.

Imagine Neiman Marcus also stocking this: ↩︎