This post should not be taken as medical advice. I am far from being a doctor. However, it might be a decent primer on inguinal hernias and their risks. Any medical questions should be directed towards your physician.

Another disclaimer: human males and females can both get inguinal hernias, but they are much, much more common in males. As a result, I wrote this post mostly with the male anatomy in mind. Those looking for hernia information more relevant to females may be interested in femoral hernias.

If any readers find inaccuracies in what follows, please let me know. I can be reached at [my first name][my last name]1[at]protonmail[dot]com

What is a hernia?

A hernia occurs when an organ partially escapes the cavity it is normally contained in. Think of a hernia as one part of your body slipping into where it’s not supposed to be. For instance, when part of your intestine is squeezed out of your abdomen and finds itself near your reproductive organs, we call that a hernia. If your stomach somehow protrudes through your diaphragm, we would also say you have a hernia, though of a separate type.

What is an inguinal hernia?

An inguinal hernia is a hernia located near the groin. (“Inguinal” is roughly Latin for groin). However, not all inguinal hernias are created equal. There are two types, indirect, and direct, with different characteristics.

Indirect inguinal hernias

In human males, we can roughly think of our intestines as living in one part of our body, and our reproductive organs living in another, separate part. These two parts are connected by a pair of small tunnels, called the inguinal canals. There is one canal on your left side, and another on your right (assuming you’re anatomically normal).

An indirect inguinal hernia occurs when part of your intestines slips through one of these tunnels and moves towards your reproductive organs. Normally, your intestines should have no access to the tunnel, (AKA the inguinal canal), but having an indirect inguinal hernia means they do. In extreme cases, your intestines can come out on the other side of the inguinal canal and hang out side-by-side with reproductive organs. In males, this means parts of the intestines will be in the scrotum, next to the testes. In females, intestines can be in the labia, greatly enlarging it. Below is a diagram describing the anatomy of indirect inguinal hernias. Ignore any medical terminology you don’t understand. What’s important is to see how the intestine can follow the path of the red arrows and end up near the teste.

To my knowledge, the greatest risk-factor for indirect inguinal hernias is genetic. In males, the testes do not begin their existence in the scrotum. Male fetuses “build” the testes in the abdomen and then have them migrate through the inguinal canal and into the scrotum before birth. In order to accommodate the testes, the inguinal canal has to widen so they can pass through. Once the passage is complete and the testes are in their new home, the canal must narrow so nothing can follow the testes into the scrotum. This is the anatomical equivalent of opening a door very wide so you can fit an elephant through, and then closing parts such that only humans can use it.

Due to genetic reasons I don’t fully understand, some male fetuses do not “close the door” of their inguinal canals well. This means the tunnel from their abdomens to their scrotums is too large, allowing their intestines to pass through and an indirect inguinal hernia to develop.

To be clear, females can also get indirect inguinal hernias, but it’s much rarer. They don’t have to get testes from their abdomens to their scrotums, so their inguinal canals either do not widen or are more effective at closing (I don’t know exactly how this works).

Direct inguinal hernias

In your body there are sheets of connective tissue called fascia. As an amateur, I think of them as the drywall of the body (and if another analogy is more apt, please recommend it). They are responsible for keeping our organs and muscles in their places.

All along our abdomen there are sheets of this fascia. However, through strain or age, the sheets may weaken. If there’s a spot that’s weak enough, it might tear, allowing some of our intestines to slip out and create a bulge in the groin area. If this happens, we call the situation a direct inguinal hernia.

A concrete example helps. Imagine a burlap bag. This is the fascia in your abdominal wall. Now, put a bunch of rope in the bag. The rope represents your intestines. A direct inguinal hernia occurs when the bag tears and a coil of rope can squeeze its way outside the bag. Below is a diagram illustrating the phenomenon in the groin. Again, ignore any medical terminology you don’t understand. Just see how the intestine is pushing through the tan-colored fascia, rather than following the inguinal canal towards the teste.

It’s worth emphasizing direct inguinal hernias have nothing to do with the inguinal canal. The intestines are not slipping through a predetermined hole to create the hernia, as in the indirect case. Instead, wear, tear, and weakness creates an opportunity for your intestine to move to a place it shouldn’t be. This is why direct inguinal hernias are associated with aging and strenuous activity.

Risks associated with inguinal hernias

Inguinal hernias may cause complications. Off the bat, having your intestines bulge out from your groin is uncomfortable. It can make physical activities, and even everyday life, painful.

There are also more serious considerations. Hernias are nearly harmless when the intestine is free to move between where it’s supposed to be and where it’s not supposed to be. In the indirect case, think of the intestine as free to move into and out of the inguinal canal, or the tunnel. In the direct case, the intestine may be able to slip into and out of the tear in the fascia, or burlap bag in our example.

Danger arises when the intestine gets stuck. If it’s lodged on the wrong side of the inguinal canal, or the tear in the fascia, the intestine is now living where it doesn’t belong. We call this scenario “incarceration” (which cracks me up) but it’s a serious problem. The intestine might kink and create a blockage which can cause severe pain and constipation. The blood supply to the intestine can also be cut off once it’s incarcerated. This is called “strangulation” and is an even greater danger. Once strangulation occurs, parts of your intestine may start to die, which can be fatal. Incarceration and strangulation are both emergency scenarios. If you have a hernia that you cannot push back into your abdomen (i.e. is incarcerated) or is painful and turning purple (is strangulating) go to the hospital immediately.

Fortunately, hernia incarceration or strangulation are relatively rare. This study followed 364 men in North America who had hernias and engaged in “watchful waiting” (AKA nothing) over the course of 2 years. Of the 364, only 2 experienced incarceration or strangulation (0.54%). The men were also on the older side, as their average age was 57.5. Another study followed 169 men with inguinal hernias over the age of 50 who waited watchfully over the course of 2 years. It saw 6 of those men have “emergent [sic?] surgery for strangulation/incarceration” (3.55%). Note that I could only find the abstract for the study. This meta-analysis claims the rate of inguinal hernia strangulation after 2 years is .27%, and after 4 years is .55%. However, I could only access the meta-analysis’ abstract, so I’m not certain what those statistics mean. I assume they started with a population of people with inguinal hernias and then checked back at the 2 and 4 year marks to see who strangulated. I’m also wary because I don’t know any characteristics of the people examined in the study.

Inguinal hernia repair

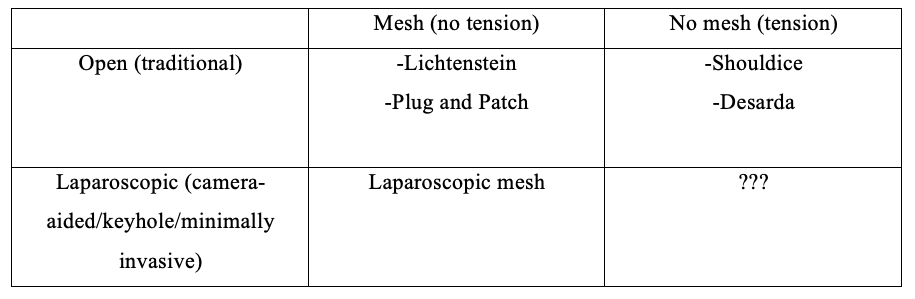

You can fix an inguinal hernia with surgery. There are many different techniques physicians can use to repair both direct and indirect hernias. The following matrix to helps keep track of the different strategies.

Very roughly, the two dimensions treatments can vary on are the way the surgery is performed (open vs. laparoscopic) and whether mesh is involved (mesh vs. no mesh).

Open surgery is what we visualize intuitively when we think of “surgery.” It involves making a relatively large incision in the body so the surgeon can directly see the problem, reach in, and fix it. When repairing inguinal hernias, open surgery usually means a 10cm incision in the groin.

Laparoscopic surgery gets its name from the laparoscope. Think of a laparoscope as a video camera on the end of a stick a surgeon can stick inside a person to see their innards. The laparoscope is very thin, meaning a surgeon can the make a small incision (~1cm) to insert the camera. Once the surgeon has a visual on the problem, she can then insert other long, thin tools into the body through similarly sized incisions. This allows her to complete an operation with only a few small incisions versus one large one.

When researching hernias, a term you’ll hear frequently is the Lichtenstein technique. This is an open surgery, and involves securing a small patch of plastic mesh in the patient to reinforce the groin area. During the operation, once the intestine is pushed back to where it’s supposed to be, the mesh is used to fence off the inguinal canal in the case of indirect hernias. In direct hernias, it gives additional strength to the fascia to prevent weakness and tears.

The “Plug and Patch” is another type of mesh repair. From what I understand, in addition to reinforcing the fascia/inguinal canal area with a flat sheet of mesh, the surgeon also stitches in a bit of mesh rolled-up into a cone shape to “plug” the weak area and provide reinforcement.

Not all strategies utilize mesh. The Shouldice technique (as I understand it) reconstructs the weakened area around the hernia by stitching together bits of your own tissue. The Desarda technique works on a similar principle, I think. I don’t entirely understand the mechanics of the non-mesh techniques. There aren’t as many accessible resources describing them online, presumably because they’re performed less often.

Note also mesh repairs can be referred to as “tension-free” and non-mesh repairs as “tension” generating. This is because when you stitch together parts of your body that weren’t attached before, you create additional tension between the parts.

Last point of this section: I think non-mesh repairs are frequently performed openly, but again I’m not entirely sure of this. From what I’ve seen, the surgeons utilizing laparoscopy to perform an operation often use mesh, but I don’t see a reason why you can’t use the Shouldice or Desarda technique using laparoscopy, either. This is why the “Laparoscopic/non-mesh” quadrant of the matrix has question marks in it. Again, this is not medical advice. It’s just me attempting to make sense of hernia repair. If you have questions, contact your doctor.

Risks of hernia repair

Every operation carries risks. There are the general risks of open surgery and the risks of a laparoscopic operation, but I’m only going to focus on those specific to hernia operations.

The most salient complication is chronic pain following an operation. Post herniorraphy pain syndrome is so common it has its own Wikipedia page. This study polled 419 patients 1 year after their operation and found ~19% reported some level of pain. 6% of those 419 described pain that inhibited daily function. Another study reached out to 464 patients 6 months after their operations and found 12.4% had moderate to severe pain. A Swedish study asked patients who underwent all different types of hernia repairs (open Lichtenstein, Shouldice, plug, laparoscopic) to rate their pain anywhere from 24-36 months after the operation. 31% of respondents reported the presence of some pain, while 6% had pain that inhibited daily function.

The Swedish study is noteworthy because it has a much larger sample size (2456 respondents) than the other studies and describes some features correlated with long-term pain. High pain levels prior to the operation, complications immediately following the operation, and being younger than 59 are all associated with persistent pain. They also found a link between lower pain and laparoscopic procedures as opposed to open ones. (Please remember these are only correlations. The authors of the study mention how more work is needed to determine whether any of these relationships are causal).

There are more dimensions to post-hernia pain. To my knowledge, researchers suspect chronic pain could be caused by nerve damage during the operation, and this can manifest in different ways. Some male patients report sexual dysfunction and ejaculatory pain following their procedure. A study in the journal Pain surveyed 1015 male patients after hernia operations and found 12.3% of them reported genital or ejaculatory pain. (12.3% is a scary number, but I’m not sure from the abstract how long after the operation the survey was administered. I wouldn’t be surprised if many male patients had genital pain a month after the procedure. However, if they’re describing pain 6 months/a year post-operation, then I’m concerned).

There are other complications that can arise from hernia operations, but I will not cover them here. Chronic pain is, I think, by far the most common issue post-operation, and probably deserves considerable attention when making a decision to operate.

Closing remarks

If you’re thinking about a hernia repair, do your own research. Consult your physician about the risks involved, the techniques your surgeon might be proficient in, and how the hernia is currently impacting your quality of life. I hope this post helped, but it is no substitute for independent reflection and medical expertise.