We begin with two questions:

- Under what conditions will a population persecute an ethnic minority during and after a pandemic?

- Who is most likely to instigate the violence?

Their answers are important. In case you haven’t heard, a deadly coronavirus has surfaced in Wuhan, China, and has now spread around the world. Some hold Asians responsible for the pandemic and act on their prejudice. A 16-year-old Asian-American boy in the San Fernando Valley was assaulted and sent to the emergency room after being accused of having the virus. In Texas, an assailant stabbed an Asian family in line at a Sam’s Club. Asians in communities like Washington D.C. and Rockville, Maryland are purchasing firearms en masse in an attempt to protect themselves. If general answers to our questions exist they may suggest ways to relieve ethnic tensions and prevent additional violence.

We turn to medieval Europe for guidance. It experienced a horrifying pandemic followed by decades of severe antisemitism. Our best bet to understand these questions is to examine the Black Plague and the subsequent treatment of medieval Jews.

The Black Plague

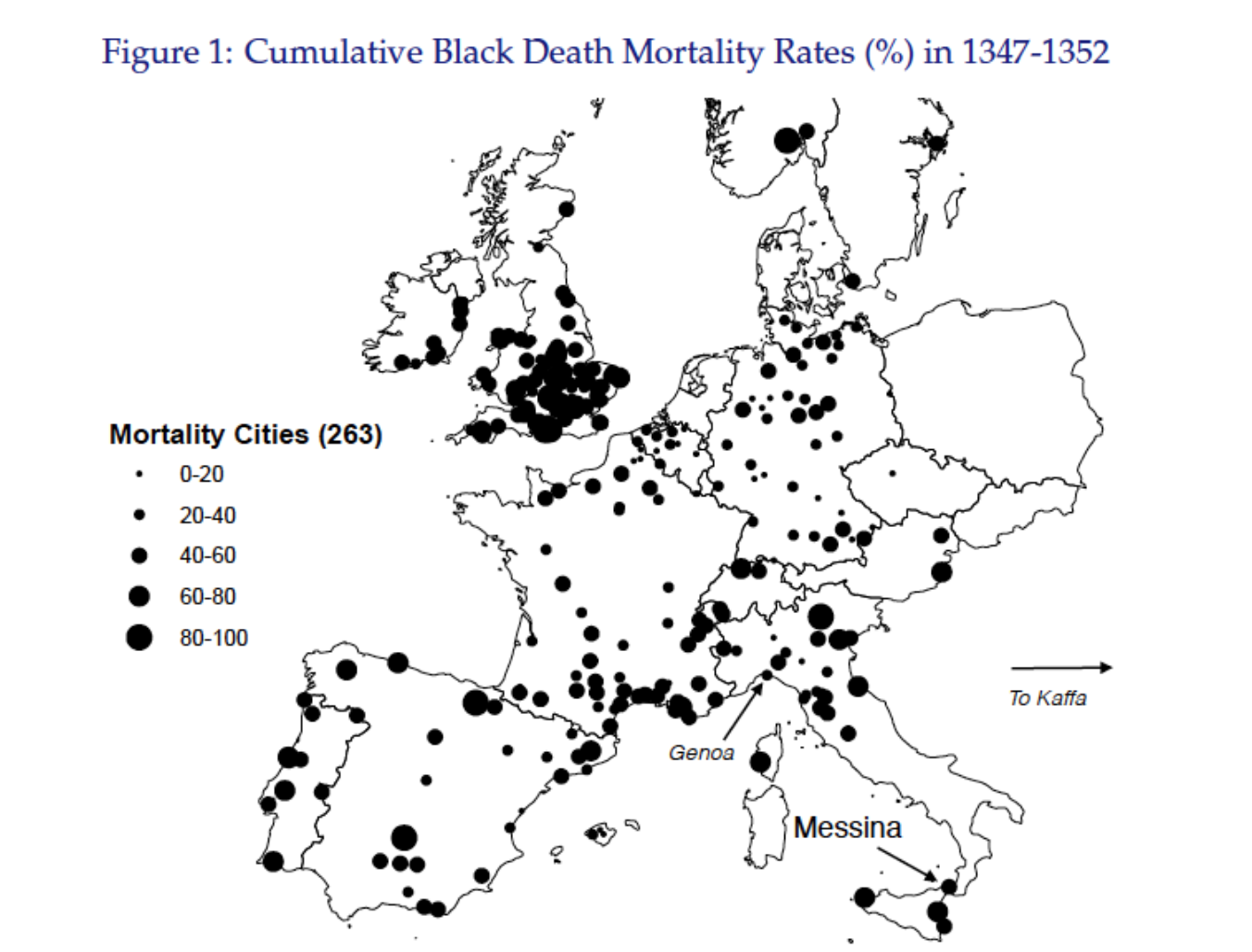

Without exaggeration, the Black Plague (also called the Black Death) was the worst pandemic in human history. From 1347, when it arrived in Italy, to 1351, between 40 and 60 percent of the entire European population perished. Aggregate figures obscure the losses of individual towns. Eighty percent of residents died in some locales, effectively wiping cities off the map (Jedwab et al., 2018). France was hit so hard that it took approximately 150 years for its population to reach pre-plague levels. Medieval historians attempted to capture the devastation of the plague by describing ships sailing aimlessly on the sea, their crews dead, and towns so empty that “there was not a dog left pissing on the wall” (Lerner, 1981).

Source: (Jedwab et al., 2018)

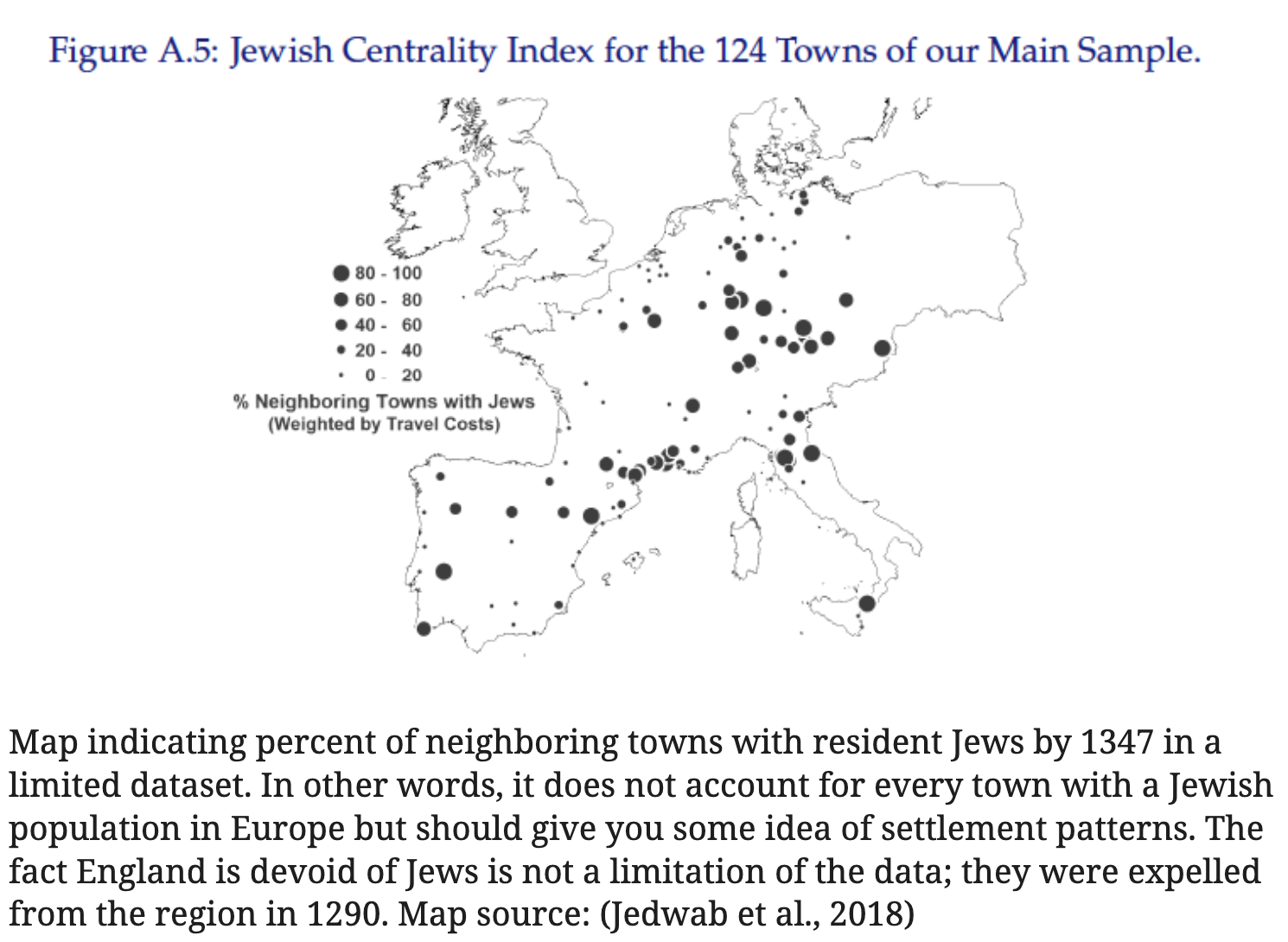

Source: (Jedwab et al., 2018)

The statistics are scary, but the plague was also visually terrifying. After catching the disease from an infected flea an individual develops black buboes (lumps) in the groin and neck areas, vomits blood, and dies within a week. In severe cases, plague-causing bacteria circulate through the bloodstream and cause necrosis in the hands and feet, leading them to turn black and die while still attached to the body. As soon as these symptoms develop, victims usually pass within 24 hours. Seeing most of your acquaintances develop these symptoms and die was arguably more psychologically damaging than actually contracting the disease yourself.

The scientific response, if it can be called one, to the pandemic was weak. Medieval medicine was still in the throes of miasma theory, which held that disease was spread by “bad air” that emanated from decomposing matter. Still, miasma was deemed an insufficient explanation for a calamity of this size. The most educated in medieval Europe saw the plague not as a natural phenomenon beyond the grasp of modern medicine, but as a cosmic indicator of God’s wrath. Chroniclers claim the plague originated from sources as diverse as “floods of snakes and toads, snows that melted mountains, black smoke, venomous fumes, deafening thunder, lightning bolts, hailstones, and eight-legged worms that killed with their stench” all ostensibly sent from above to punish man for his sins (Cohn, 2002). A common addendum was that these were all caused in one way or another by Jews, but we’ll get to that later.

Some explanations, if squinted at, bear a passing resemblance to the secular science of today. They invoked specific constellations and the alignment of planets as the instigators of the plague, drawing out an effect from a non-divine cause. How exactly distant celestial objects caused a pandemic is unclear from their accounts, though.

In general, medieval explanations of the plague reek of desperate mysticism. They had quite literally no idea of where the disease came from, how it worked, or how to protect themselves from it.

Medieval Jews

Jewish communities were widespread in Europe by the time the plague began. In the eighth century, many Jews had become merchants and migrated from what we today call the Middle East to Muslim Spain and southern Europe. Over the next two centuries, they spread northward, eventually reaching France and southern Germany before populating the rest of the region (Botticini & Eckstein, 2003). Jews were overwhelmingly located in large urban centers and specialized in skilled professions like finance and medicine. By the 12th century, scholars estimate that as many as 95% of Jews in western Europe had left farming and taken up distinctly urban occupations (Botticini & Eckstein, 2004).

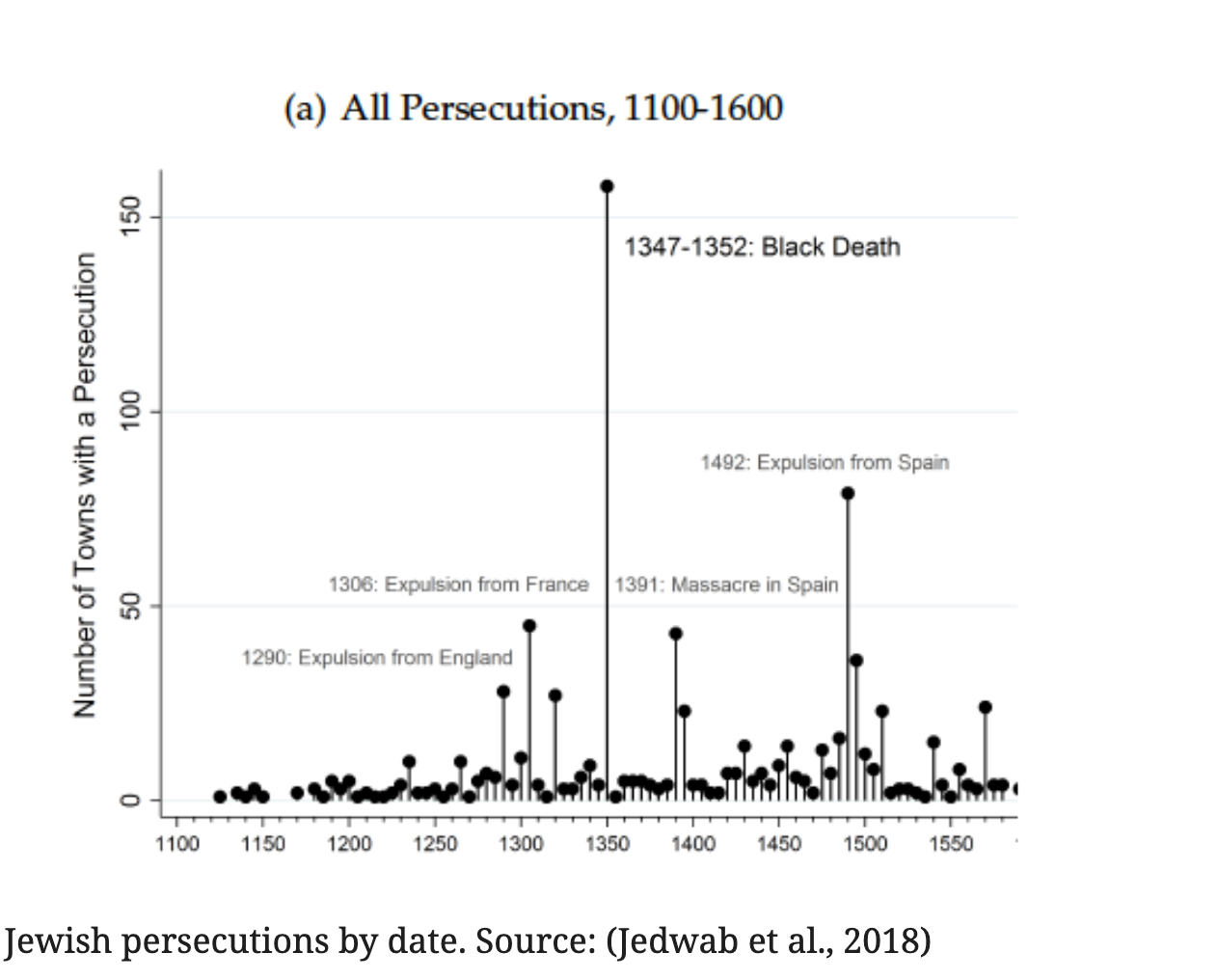

Unfortunately, the medieval period offered Jews little respite from persecution. Antisemitism was constant and institutionalized, as Christianity was the official religion of most states. Restrictions were placed on the ability of Jews to proselytize, worship, and marry. For example, in 1215, the Catholic Church declared that Jews should be differentiated from the rest of society via their dress to prevent Christians and Jews from accidentally having “sinful” intercourse. These rules eventually begot requirements that Jews wear pointed hats and distinctive badges, foreshadowing the infamous yellow patches of the Holocaust.

Medieval antisemitism was violent as well as bureaucratic. Pope Urban II fueled Christian hysteria by announcing the First Crusade in 1096, and shortly after, bands of soldiers passing through Germany on their way to wage holy war in Jerusalem killed hundreds of Jews in what became known as the Rhineland Massacres. These attacks were so brutal that there are accounts of Jewish parents hearing of a massacre in a neighboring town and killing their own children, and then themselves, rather than face the crusaders. Explanations for these massacres vary. Some scholars claim they were fueled by the desire to seize the provisions of relatively wealthy Jews in preparation for travel to the Middle East. Others attribute them to misplaced religious aggression intended for Muslims but received by Jews due to their proximity and status as “non-believers.” While there are earlier recorded instances of antisemitism, the pogroms of the First Crusade are believed to represent the first major instance of religious violence against the Jews.

Strangely, the Medievals seem to vacillate between ethnic loathing and appreciation for Jewish economic contributions. The Catholic Church forbade Christians from charging interest on loans in 1311, allowing Jews to dominate the profession. As a result, they were often the only source of credit in a town and hence were vital to nobility and the elite. This, coupled with Jews’ predilection to take up skilled trades, gave leaders a real economic incentive to encourage Jewish settlement. Rulers occasionally offered Jews “promises of security and economic opportunity” to settle in their region (Jedwab et al., 2018).

The Black Plague and Medieval Jews

As mentioned, the plague was a rapid, virulent disease with no secular explanation, and the Jews were a minority group—the only non-Christians in town—with a history of persecution. Naturally, they were blamed. Rumors circulated that Jews manufactured poison from frogs, lizards, and spiders, and dumped it in Christian wells to cause the plague. These speculations gained traction when tortured Jews “confessed” to the alleged crimes.

The results were gruesome. Adult Jews were often burned alive in the city square or in their synagogues, and their children forcibly baptized. In some towns, Jews were told they were merely going to be expelled but were then led into a wooden building that was promptly set ablaze. I will spare additional details, but these events spawned a nauseating genre of illustrations if one is curious. As the plague progressed, more than 150 towns recorded pogroms or expulsions in the five-year period between 1347 and 1351. These events, more so than the Rhineland massacres, shaped the distribution of Jewish settlement in Europe for centuries afterward.

If we can bring ourselves to envision these pogroms, we imagine a mob of commoners whipped up into a spontaneous frenzy. Perhaps they have pitchforks. Maybe they carry clubs. Given what we know about the economic role of medieval Jews, you might impute a financial motive upon the villagers. It’s possible commoners owed some debt to the Jewish moneylenders that would be cleared if the latter died or left town. If asked what income quintile a mob member falls into, you might think that’s a strange question, and then respond the lowest. Their pitchforks indicate some type of subsistence farming, and only the poorest and least enlightened would be vulnerable to the crowd mentality that characterizes such heinous acts, you would think.

If so, it might be surprising to hear the Black Death pogroms were instigated and performed by the elite of medieval society. (Cohn, 2007) writes that “few, if any, [medieval historians] pointed to peasants, artisans, or even the faceless mob as perpetrators of the violence against the Jews in 1348 to 1351.” Bishops, dukes, and wealthy denizens were the first to spread the well-poisoning rumors and were the ones to legally condone the violence. Before even a single persecution in his nation took place, Emperor Charles IV of Bohemia had already arranged for the disposal of Jewish property and granted legal immunity to knights and patricians to facilitate the massacres. When some cities expressed skepticism at the well-poisoning allegations, aristocrats and noblemen, rather than the “rabble,” gathered at town halls to convince their governments to burn the Jews. Plague antisemitism, by most accounts, was a high-class affair.

Mayors and princes recognized the contagious nature of violence. If elites persecuted the Jews, they thought, the masses might join in and the situation could spiral out of control. As a result, the wealthy actively tried to exclude the poor from antisemitic activities. Prior to a pogrom, the wealthy would circulate rumors of well-poisoning. Those of means would then capture several Jews, torture them into “confessing,” and then alert the town government. Its notaries would record the accusations, and the matter would be presented before a court. After a (certain) guilty verdict, patrician leaders would gather the Jews and burn them in the town square or synagogue. Each step of the process was self-contained within the medieval gentry, providing no opportunity for commoners to amplify the violence beyond what was necessary. Mass persecutions often take the form of an entire society turning against a group, but the medieval elites sought to insulate a substantial amount of their population from the pogroms. Ironically, they feared religious violence left unchecked.1

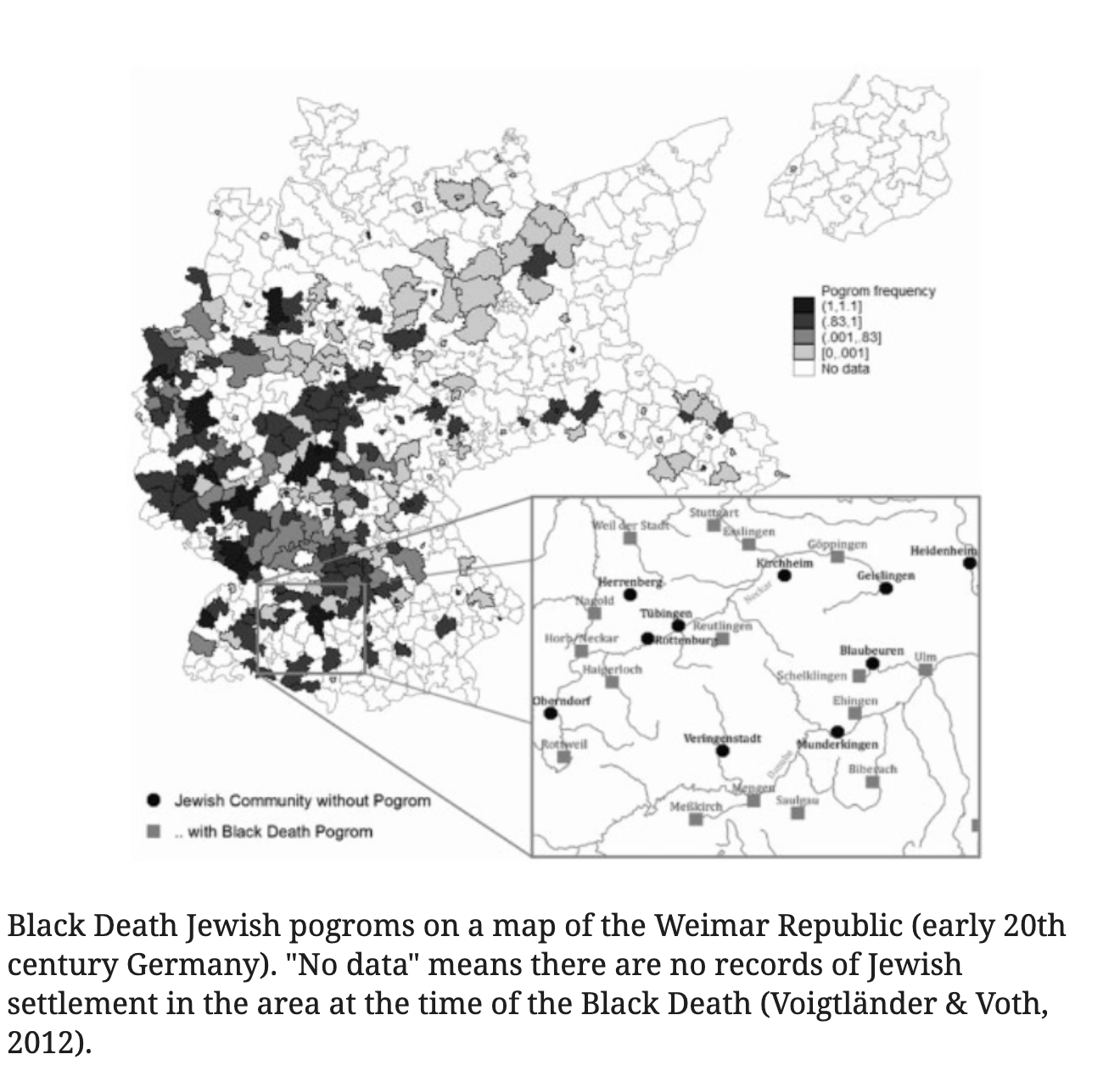

Persecutions were widespread, but not universal. (Voigtländer & Voth, 2012) say only 70 percent of towns with a Jewish population in plague-era Germany either expelled or killed their Jews. To be sure, 70 percent is a substantial figure, but the fact it is not 100 percent demonstrates that there were conditions under which ethnic violence would not ensue. What were these conditions?

In pursuing this question, (Jedwab et al., 2018) observed something strange. As plague mortality increased in some towns, the probability Jews would be persecuted actually decreased. A town where only 15 percent of inhabitants died is somehow more antisemitic than one where 40 percent did. How odd. Common sense tells us that the more severe an unexplained disaster, the stronger the incentive to resolve ambiguity and blame an outgroup. Why reserve judgment when things are the worst?

It turns out economic incentives were stronger than the desire to scapegoat. Jedwab only observed the inverse relationship between mortality and probability of persecution in towns where Jews provided moneylending services. The Jews’ unique economic role granted them a “protective effect,” changing the decision calculus of would-be persecutors. It’s true there’s still an incentive to persecute Jews since debts would be cleared if the moneylenders died, but this is a short-term gain with long-term consequences. If all Jews in a town are eliminated then future access to financial services is gone. Everyone in town would be a Christain, and thus forbidden from extending credit. As mortality increases, Jews qua moneylenders became increasingly valuable, since killing or expelling them would exacerbate the economic crisis that accompanies losing a significant fraction of your population. As a result, they were spared. 2

This is consistent with the picture we developed earlier of the upper classes undertaking plague pogroms. Often, only the wealthy utilized Jewish financial services, thus only they were sensitive to the financial implications of killing the sole bankers in town (Cohn 2007). If commoners were the major perpetrators of Black Death massacres, Jedwab and colleagues would probably not encounter evidence of a protective effect tied to Jewish occupations. Indeed, they looked for, and could not find, the protective effect in towns where Jews were doctors, artisans, or merchants. It only appeared when they provided financial services.

Persecution frequency also fell dramatically after the initial wave of the plague. The disease made semi-frequent appearances in the decades and centuries after 1347, but not one of them sparked as much violence as the first bout. A potential explanation is that many Jews had already been killed or expelled from their towns, leaving nobody to persecute. Plague severity was lower in later recurrences, so there might have been less of an incentive to persecute a minority for a mild natural disaster as opposed to a major one.

I’ll describe a somewhat rosier phenomenon that could have contributed to this decline in persecutions. Remember that the medieval intellectual elite was clueless when it came to the causal mechanisms of the plague. Among other theories, they believed it spread via bad air, worm effluvium, frogs and toads that fell from the sky, the wrath of God, or Jewish machinations. Because Jews were the only salient member of this list present in most towns, they had borne the brunt of popular frustration and become a scapegoat .3

Yet, science progressed slowly. By 1389, roughly 40 years after Europe’s first encounter with the plague, doctors noticed that mortality had fallen after each successive recurrence of the disease. Instead of attributing this to fewer toads in the atmosphere or less worm stench, they settled on the efficacy of human interventions. Institutions had learned how to respond —the quarantine was invented in this period— and medicine had progressed (Cohn 2007). Medievals had increasingly effective strategies for suppressing the plague and none of them involved Jews. Blaming them for subsequent outbreaks would be downright irrational as you would be diverting time and resources away from interventions that were known to work.

I want to be clear that this did not end antisemitism in Europe. Jews for centuries were —and still are— killed over all types of non-plague related allegations like host desecration, blood libel, and killing Jesus. Yet, they enjoyed a period of relative calm after the first wave of the Black Death, in part, I believe, because their persecutors had begun to understand the actual causes of the disease.

Generalizations

- Under what conditions will a population persecute a minority?

Persecutions are more likely when members of the minority in question don’t occupy an essential economic niche. Jews as moneylenders provided a vital service to members of the medieval elite, so the prospect of killing or expelling their only source of credit may have made them think twice about doing so.

- Who is most likely to instigate the violence?

Wealthy, high-status members of medieval society instigated and undertook the Black Plague pogroms. They were responsible for spreading well-poisoning rumors, extracting “confessions,” processing and ruling on accusations, and attacking Jewish townsfolk. Some medieval elites even conspired to insulate the poor from this process for fear of the violence escalating beyond control.

How applicable are these conclusions? Can they tell us anything specific about ethnic violence and COVID-19?

Probably not. For starters, the world today looks nothing like it did during the 14th century. The Medievals may have discovered how to attenuate the effects of the plague, but it remained more or less a mystery for centuries afterward. We didn’t get germ theory until the 19th century, and it wasn’t until 1898 that Paul-Louis Simond discovered the plague was transmitted to humans through fleas.

Perhaps as a result of scientific progress, we’re also much less religious, or nature of our religiosity has changed. Very few believe hurricanes are sent by God to punish sinners, and we don’t supply theological explanations of why the ground trembles in an earthquake. We have scientific accounts of why nature misbehaves. As a result, we’re skeptical of (but not immune to) claims that a minority ethnic group is the source of all our problems. In short, we have the Enlightenment between us and the Medievals.

Cosmopolitanism is also on our side. Jews were often the only minority in a town and were indistinguishable without special markers like hats and badges. To this day, parts of Europe are still pretty ethnically homogeneous, but every continent has hubs of multiculturalism. 46 percent of people in Toronto were born outside Canada. 37 percent of Londoners hail from outside the UK. Roughly 10 percent of French residents are immigrants. All this mixing has increased our tolerance dramatically relative to historical levels.

Perhaps most importantly, COVID-19 is not even close to the plague in terms of severity. The medical, economic, and social ramifications of this pandemic are dire, but we are not facing local death rates of 80 percent. We do not expect 40 to 60 percent of our total population to die. COVID-19 is a challenge that is taxing our greatest medical minds, but we have a growing understanding of how it functions and how to treat it. It’s definitely worse than the flu, but it’s no Black Plague.

An investigation into the Black Plague and medieval Jews can provide historical perspective, but its results are not easily generalizable to the current situation. The best we can say is that when things are bad and people are ignorant of the causes, they will blame an outgroup they do not rely on economically. The cynical among us perhaps could have intuited this. Thankfully, things aren’t as bad now as they were in 1347, and we are collectively much less ignorant than our ancestors. We’ve made progress, but intolerance remains a stubborn enemy. What Asians already have, and will, endure as a result of this pandemic supports this.

Acknowledgments

Huge thanks to Michael Ioffe and Jamie Bikales for reading drafts.

Still, the class demographics of medieval pogroms are a matter of scholarly debate. (Gottfried, 1985) describes members of Spanish royalty unsuccessfully attempting to protect their Jewish denizens. However, he does not specify whether the antisemitism was primarily instigated by the masses or regional leaders. (Jedwab et al., 2018) mentions “citizens and peasants” storming a local Jewish quarter, but whether local antisemitism was spurred by the gentry or not is also unclear. (Haverkamp, 2002) supposedly also argues for the commoner-hypothesis, but the article is written in German and thus utterly inaccessible to me.

What I cited

(These are all the scholarly sources. My guideline is that if I downloaded something as a pdf and consulted it, it’ll be here. Otherwise, it’s linked in the text of the post).

Botticini, M., & Eckstein, Z. (2003, January). From Farmers to Merchants: A Human Capital Interpretation of Jewish Economic History.

Botticini, M., & Eckstein, Z. (2004, July). Jewish Occupational Selection : Education, Restrictions, or Minorities? IZA Discussion Papers, No. 1224.

Cohn, S. (2002). The Black Death: End of a Paradigm. American Historical Review .

Cohn, S. (2007). The Black Death and the Burning of Jews. Past and Present(196).

Gottfried, R. S. (1985). The Black Death: Natural and Human Disaster in Medieval Europe. Free Press.

Haverkamp, A. (2002). Geschichte der Juden im Mittelalter von der Nordsee bis zu den Su¨dalpen. Kommentiertes Kartenwerk. Hannover, Hahn.

Jedwab, R., Johnson, N. D., & Koyama, M. (2018, April). Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death. SSRN.

Kieckhefer, R. (1974). Radical tendencies in the flagellant movement of the mid-fourteenth century. Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 4(2).

Lerner, R. E. (1981, June). The Black Death and Western European Eschatological Mentalities. The American Historical Review, 533-552.

Voigtländer, N., & Voth, H.-J. (2012). PERSECUTION PERPETUATED: THE MEDIEVAL ORIGINS OF ANTI-SEMITIC VIOLENCE IN NAZI GERMANY*. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1339-1392.

-

I draw heavily on (Cohn, 2007) in the preceding two paragraphs. It’s definitely true some pogroms were instigated and undertaken by the poor while the elites sought to protect the Jews. For instance, Pope Clement VI issued an (unheeded) papal bull absolving Jews of blame. Yet, Cohn has convinced me (an amateur) that these cases constitute a minority. ↩︎

-

A simple alternate explanation for the inverse relation between mortality and probability of persecution is that there are fewer people left to facilitate a pogrom or expulsion at higher levels of mortality. Jedwab and colleagues aren’t convinced. They note that the plague remained in a town for an average of 5 months, and people weren’t dying simultaneously. It’s entirely possible that even at high mortality a town can muster enough people to organize a pogrom. Also, many of the persecutions were preventative. Some towns burned their Jewish population before the plague had even reached them in an attempt to avert catastrophe. ↩︎

-

God was also “present” —in the form of churches and a general religious atmosphere— in medieval Europe, so he was another popular figure to attribute the plague to. However, you can’t really blame God in a moral sense for anything he does, so adherents to this view blamed themselves. So-called “flagellants” traveled from town to town lashing themselves in an attempt to appease God’s wrath and earn salvation. This was strange and radical even by medieval standards. Pope Clement thought the movement heretical enough to ban it in 1349 (Kieckhefer 1974). ↩︎