I used to have this idea that the introduction of electric appliances circa 1960 dramatically reduced the number of hours people, especially housewives, spent on domestic tasks. The thought is pretty intuitive. It’s quicker to wash clothes with a washing machine than with a tub and washboard. Dishwashers are more efficient than washing dishes by hand. In the span of a couple of years, I thought, American housewives had much more free time. This idea fits nicely with the fact women’s workforce participation rate increased in the 1960s and the decade marked the beginning of second-wave feminism. Just perhaps, a decrease in the domestic load allowed women time to reflect on unjust norms and mobilize against them.

Unfortunately, the data do not support me. Household appliances are not the fiery instruments of social change I imagined them to be. There is no doubt they altered American domestic life, but they did not reduce the aggregate time spent on household duties.

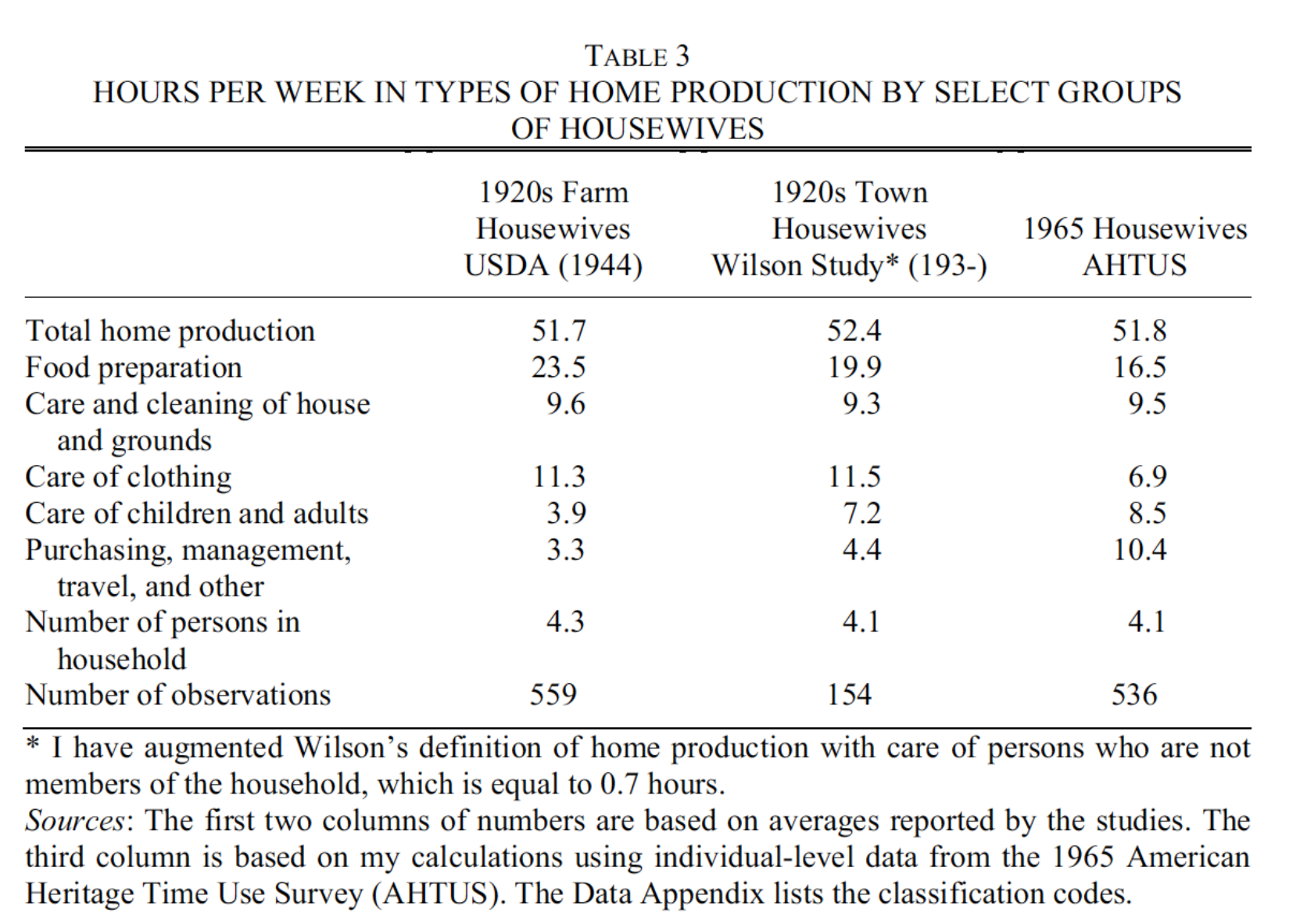

Several time-use studies from 1925 to 1965 corroborate this.

Source: (Ramey 2009)

As we can see, total home production, or the amount of time housewives spent on domestic tasks, remained approximately constant from the 20s to the 60s. This is surprising considering home appliances diffused rapidly during this period. In 1925, fewer than 20% of American households had a washing machine. By 1950, more than 75% of them did (Bowden and Offer 1994).

However, the allocation of time had changed between the decades studied. Hours spent in food preparation and care of clothing decreased and were shifted towards general managerial tasks (purchasing, management, travel, and other). We can imagine appliances and relying more on store-ready food contributing to decreases in food-prep time for the 1960s housewife. We can also imagine frequent trips to the grocer increasing the time spent on travel, for example.

Even the presence of basic utilities didn’t seem to decrease time spent on domestic duties. Time-use studies comparing black and white families in the 1920s reach surprising results. Black housewives at the time, most without the luxury of a kitchen sink or running water, spent just as many hours on housework as their white counterparts. Both parties averaged around 53 hours a week. As it turns out, time spent on household production is not correlated with income (which is —most likely— correlated with the amount of technology in the home). How could this be? (Ramey 2009) explains:

[Since] lower income families lived in smaller living quarters, there was less home production to be done. Reid argued that apartment dwellers spent significantly less time in home production than families in their own houses; there was less space to clean and no houses to paint or repair. Second, there is a good deal of qualitative evidence that lower-income families produced less home production output. A home economist noted during that time “if one is poor it follows as a matter of course that one is dirty.” Having clean clothes, clean dishes, a clean house, and well-cared-for children was just another luxury the poor could not afford.

There are additional historical factors that explain why household production did not decrease with the introduction of appliances. The first views appliances as a substitute for another labor-saving device whose availability was dwindling: servants. In the early 20th century, it was common for middle-class housewives to hire help. Servants and maids assisted with cooking, cleaning, and caring for children, among other things. Foreign-born residents were usually employed in this capacity, but when immigration restrictions were imposed, domestic labor became scarce. The decline in servants and maids coincided with the rise of electrification and home appliances, allowing a single woman to accomplish what used to take a staff of two or three servants to do (Ramey 2009). Appliances, in this sense, compensated for the loss of a maid. Perhaps it used to take an hour for you and two servants to do the laundry. With a laundry machine, it’s now possible to do the laundry by yourself in an hour. Time spent in home production remains the same, but there are now fewer “inputs” to the process.

The second explanation appeals to changing standards. While appliances were being introduced to American families, new ideas about sanitation and nutrition were also spreading. Housewives learned they could positively influence the health and well-being of their family through their housework, so they opted to do more of it (Mokyr 2000). Even though they could have cleaned the house or cooked dinner much quicker than before, housewives decided to keep cleaning, or cook a more demanding meal, rather than take the time saved by appliances as leisure.

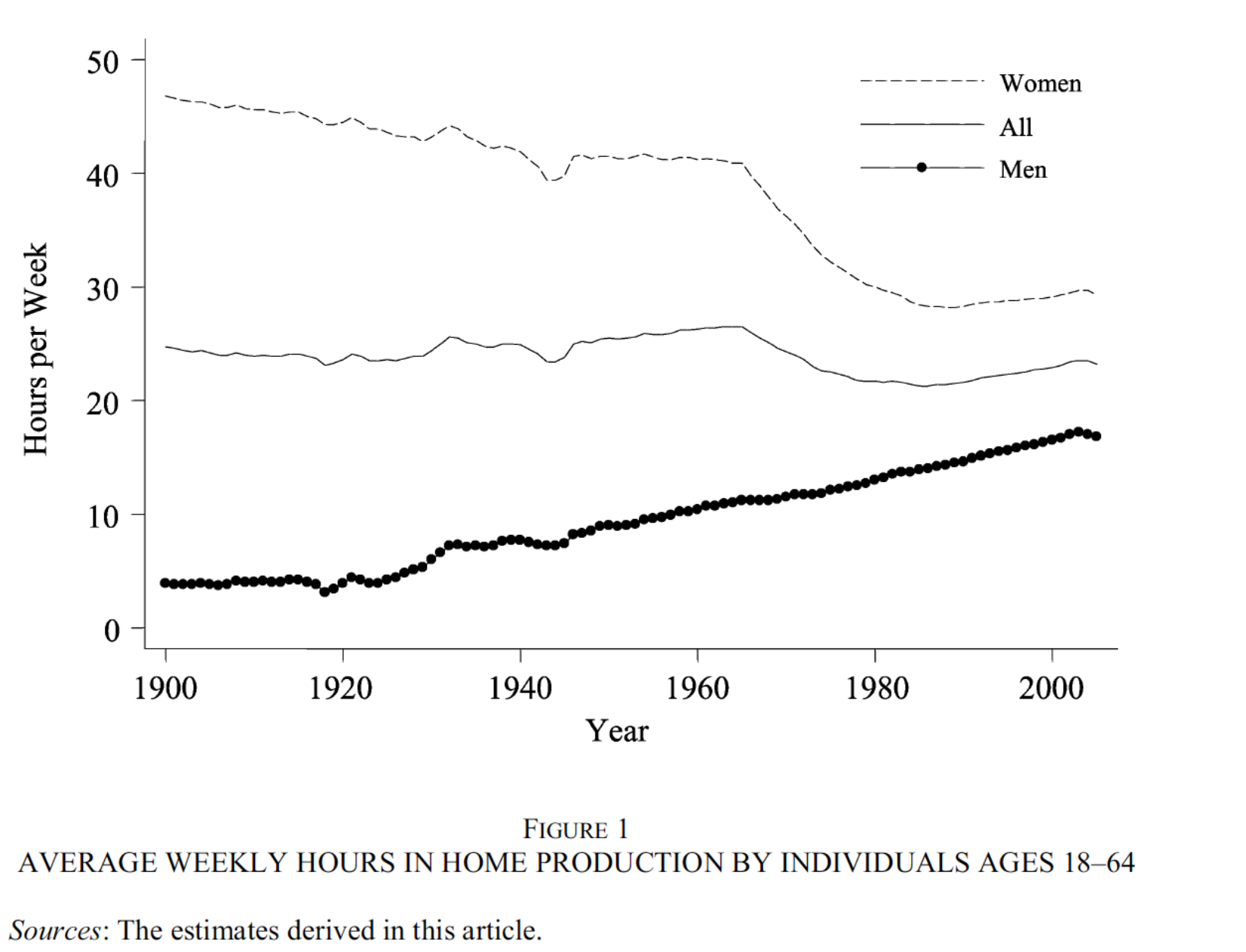

Do not fear. Hours spent in home production by women did begin to decrease near the end of the 1960s. Yet, this was not due to advances in labor-saving technology.

Source (Ramey 2009)

Men began to contribute more. As a result, the average woman devoted only 30 hours per week hours towards household production in 2005, compared to the ~50 hours she may have expended in 1900. However, total hours spent in home production per week, the sum of male and female hours, has not shifted much over the century. The average person today is likely devoting as much time towards domestic tasks as their ancestors did over 100 years ago.

–

I think there are potential implications here for thinking about the future. Many of us imagine that advances in technology will increase productivity dramatically, and as a result, we will be able to enjoy much more leisure. If we can accomplish in 20 hours what it used to take 40 hours to do, why work the additional 20 hours?

Yet, history suggests that advancements in domestic technology do not necessarily save us time. Their benefits roll over into things like increasing living standards before we see additional leisure. Standards for health and cleanliness may increase steadily as our capacity for nutritious meals and clean homes increases as well. Perhaps something vaguely similar to the immigrant/servant situation could happen. Innovations in household technology might decrease time spent in home production, but maybe our jobs become incredibly demanding, eating any time saved by being able to cook or clean quicker. In both scenarios, leisure loses.

I don’t think this is disheartening news. Recall the black and white families studied in the 1920s. Even though housewives of both races spent approximately the same amount of time on household production, the white families were much better off. They enjoyed a higher standard of living due to basic utilities like running water and probably also other bits of technology present in their homes. Even though inputs, in terms of hours expended, are similar, the difference in outputs is astounding.

As a result, a more realistic version of the future might still have ~50 hours of home production for each household, but living standards that are much, much higher. Our health will be fantastic, we will conform to the highest standards of sanitation and hygiene, and we will unequivocally be better off, leisure be damned. We imagine an ideal future as a place with infinite leisure, but a society in which our standard of living is ten times as high with us putting in the same amount effort is still pretty damn good.

Sources

Bowden, S., & Offer, A. (1994, November). Household Appliances and the Use of Time: The United States and Britain Since the 1920s. The Economic History Review, 725-748.

Mokyr, J. (2000). Why “More Work for Mother?” Knowledge and Household Behavior, 1870-1945. The Journal of Economic History.

Ramey, V. (2009, March). Time Spent in Home Production in the Twentieth-Century United States: New Estimates from Old Data. The Journal of Economic History, 1-47.