In part 1, we described the hypothetical students used in this investigation and calculated the opportunity cost of going to law school for each of them. In part 2, we factored in tuition and university fees and arrived the amount of income a new JD would need to earn to do “better” than their non-lawyer doppelgänger. Part 3 is where we draw conclusions. In order to do so, we’re going to revisit the concept of hurdle compensation that we developed in the last post.

Step 5: hurdle compensation, attribution, and expected salary

As mentioned above, a student’s hurdle compensation is the annual salary they would need to exceed in order to do “better” than they would have without a JD. While this figure tells us something about the costs of actually being a lawyer and how much one should earn to be better off financially in light of these costs, we can interpret it in another manner. Whatever one of our students earns in excess of their hurdle compensation is income directly attributable to their law degree.

Think about how the hurdle compensation was calculated. We took the expected fourth year non-JD income of one of the students and added overtime pay. This is pay they could have earned at their hypothetical non-lawyer jobs, meaning anything in excess is a result of their law degree. The cost of living premium is still included even though it does not represent income a student could have earned in an alternate life. It accounts for the fact some of their salaries as lawyers will be eaten up by higher than average housing.

Now, we examine each students’ expected post-JD income and see how it compares to their hurdle compensation.

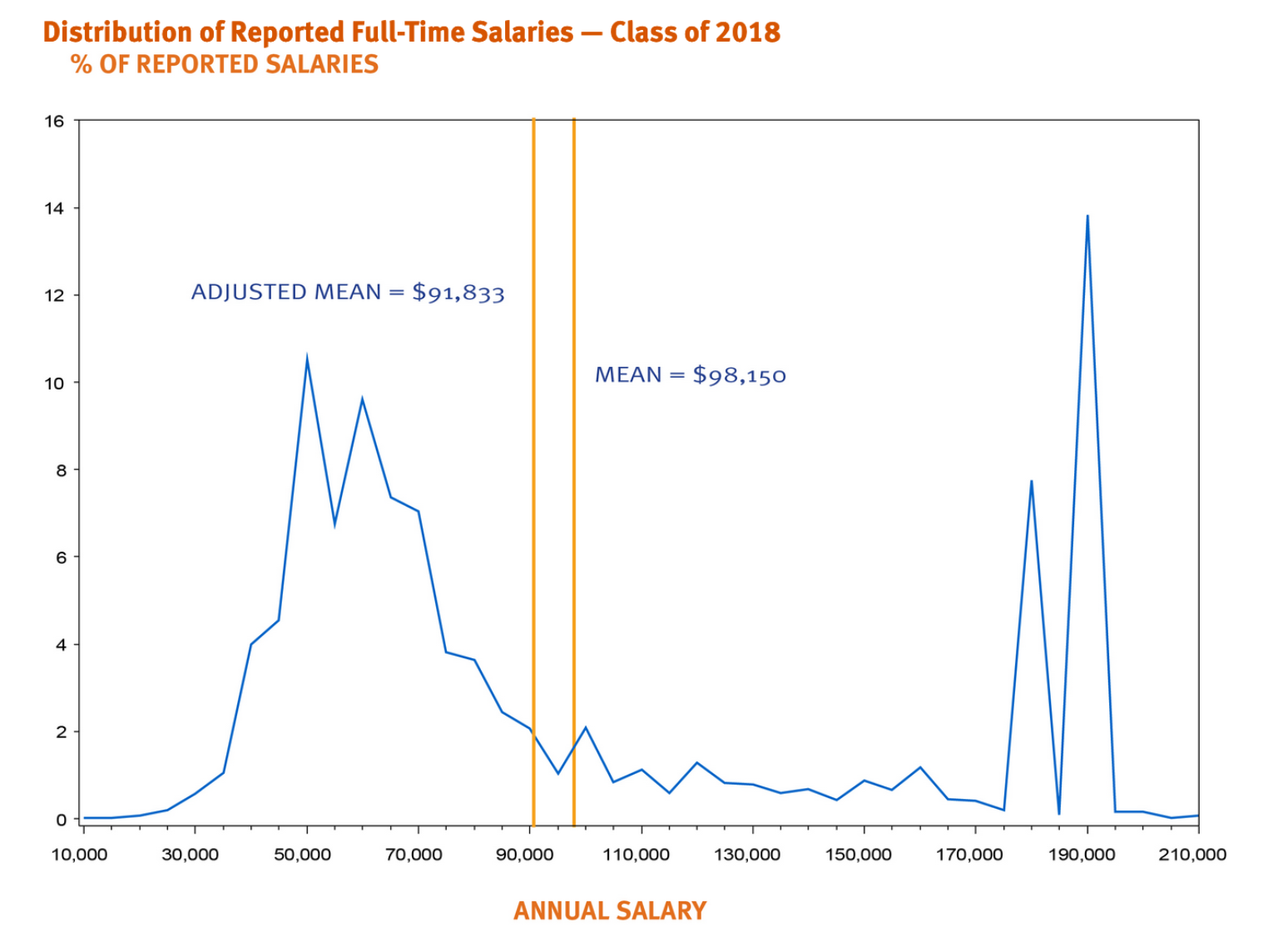

Fortunately, we have good data on salaries for recent law graduates. For more than a decade, the National Association for Law Placement (NALP) has been surveying newly employed lawyers on their earnings and publishing the results. Schlunk used their 2008 report to do his analysis and I will use the 2018 data for mine.

As we can see, the distribution of lawyer salaries is heavily concentrated in two areas. The NALP asserts 49.6% of salaries reported fall in the $45,000-$75,000 range, while just over 20% are greater than $180,000. As you can guess, the salaries in the high six figures are those given to new biglaw associates. The NALP also notes low salaries are under-reported, meaning the percentage of jobs paying in the 45-75k range is probably higher.

Based off of this graph, we will assume the average non-biglaw job pays $60,000 and the average biglaw one $185,000. Using the percentage chance we stipulated in part 1 of each student landing a biglaw job, we can calculate their expected first year salary and subtract their hurdle compensation to see how much income is attributable to their JD.

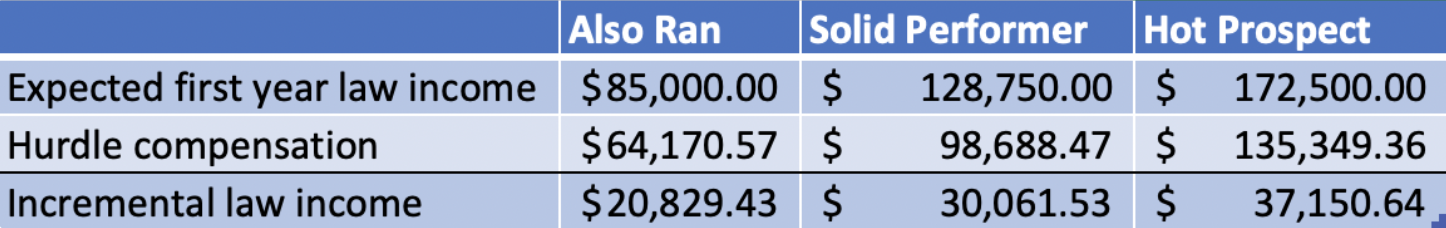

table 8

table 8

Thankfully, the results are positive. The expected income of each student exceeds their hurdle compensation, meaning on average their degree is conferring some additional financial gain. However, we must note averages can be deceiving. Solid Performer’s expected income is ~$129,000, but this is nowhere near what he will earn in the average biglaw or non-biglaw job. If he is unfortunate enough to find employment in the 60-75k range (as nearly half of all new lawyers do) his annual earnings will not exceed his hurdle compensation of ~$99,000. His law degree may have made him eligible for high paying biglaw jobs, but the alternatives are dismal given the costs. In the event he doesn’t score a biglaw job (a 45% chance), he will be worse off than if he never went to law school in the first place.

Regardless, we are going to treat the expected first year law income as the actual earnings of our students, and their incremental income as the actual income of theirs attributable to a law degree even if in specific cases the numbers may either be much higher or much lower.

Step 6: discount rates

As of now, we know what a law degree will net you your first year of employment, but what about all subsequent years until retirement? Even if we did know that, how can we value future income in today’s terms to compare it to the costs we’ve incurred in the present?

The first question we’ll tackle with an assumption. In his calculations, Schlunk assumes a 3.5% yearly growth in salary over a 35 year law career to account for increases in productivity. I see no reason to disagree, so I’ll do the same. This ignores the possibility of our students making partner or coming across fat bonuses or raises, though.

Techniques exist to answer the second question. Valuing future income isn’t as straightforward as summing it all and saying this is how much it’s worth (unless you’ve made some uncommon assumptions). Future earnings are discounted and expressed in present dollar terms in order to reflect the opportunity cost of not having the money or account for some risk to actually receiving it.

The latter reason is most relevant to our discussion. The incremental income earned attributable to the law degree is small, relative to the entire salary, and volatile. Schlunk says law students often do not appreciate the career instability of many attorneys. Not everyone gets raises and sometimes law firms “blow up.” Even if you’re an in-house lawyer, you’re as subject to corporate downsizing as any other employee.

Additionally, our students aren’t content with merely breaking even on this investment. They want as close to a guarantee as possible they will not only recoup their initial costs but make positive returns. We can think about this as them wanting the investment to pay off over a very short time horizon, which is the equivalent of applying a high discount rate to future income. Money closer to the present is much, much more valuable to them. The more they make now, the less doubt there is that law school was a bust.

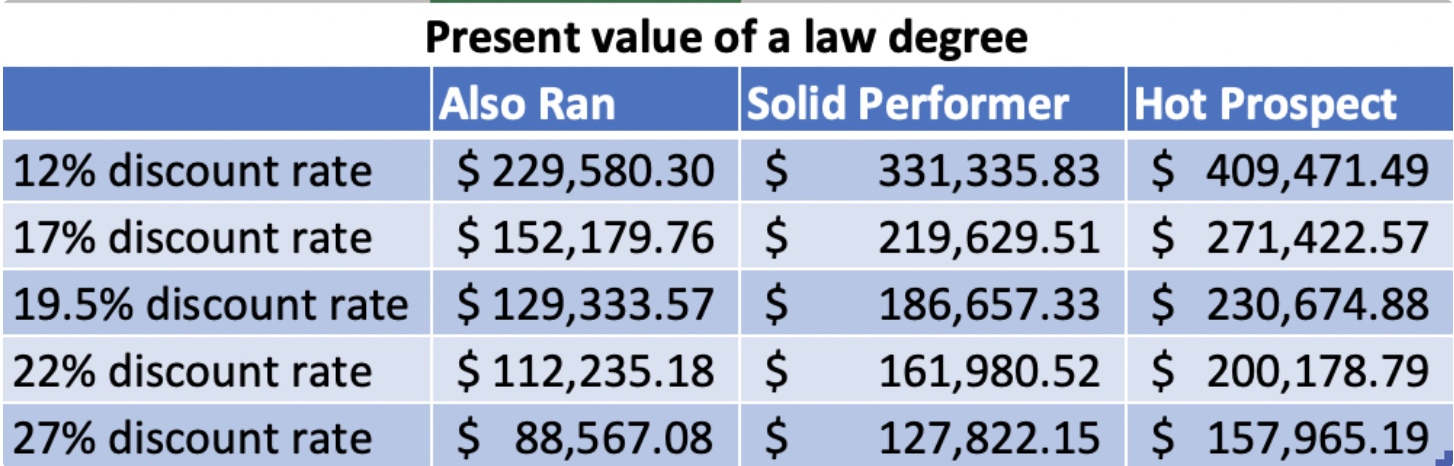

These two factors make it reasonable to apply relatively high discount rates to the future income attributable to the degree. To do our calculations, we will treat each student’s incremental income as an annuity dispersed once a year that grows at a rate of 3.5%. Below are the results for different discount rates.

table 9

table 9

Step 7: conclusions and limitations

For context, I’ll reproduce the cost of attendance for each student.

table 10

table 10

For all of the given discount rates, law school is not an attractive investment. Suppose Solid Performer personally discounts future income at 17%. In other words, $100 today is worth just as much as $117 a year from now for him. If he were to attend law school under our assumptions, he would be paying $335,579 (total cost) for something that is in fact only worth $219,629 to him. Likewise, If Hot Prospect is under the impression that 12% is the correct rate (which is still significantly below Schlunk’s recommendations), she would be paying $422,140 for something that is worth $409,471. Each student would only break even if they convinced themselves something a little under 12% was the appropriate discount rate.

Does this mean law school is a poor investment in all circumstances? Definitely not. One thing our analysis neglects is the impact of financial aid and scholarships on total cost. Many law schools offer considerable assistance to students, with more than half of their enrollment receiving some type of merit or need-based funding. Clearly, the conversation surrounding law school changes significantly when you’re on a full ride versus paying entirely out of pocket.

It’s also worth repeating how averages can be deceiving. Our expected yearly income figure used to calculate the present value of a law degree captures only the average outcome of each student. We’ve assumed Solid Performer either earns $60,000 or $180,000 out of law school, but used something in between these two numbers to arrive at the salary we claim he would have made after graduation. If Solid Performer gets the biglaw job and earns the $180,000, his degree is certainly a much better financial investment, but that is not reflected in our outcomes.

The next set of limitations has to do with your author. I am an undergraduate with some time on his hands, not Herwig Schlunk, a law professor with more degrees than everyone in my family combined. The assumptions I make in this series of posts without Schlunk’s guidance are at best educated guesses and at worst ignorant stipulations. What’s more, even though I am trying my best to follow Schlunk’s analysis closely, his paper is nearly a decade old and I do not have the expertise to know to what extent his methods and assumptions are still accurate. This is an amateur attempt at something only a professional can treat with the necessary discernment.

Lastly, I expect some to take issue with the scope of this inquiry. I’ve tried to shed light on the narrow question of whether or not law school is a good financial investment, but there are clearly other reasons to be a lawyer. As mentioned in the intro to part 1, one can be motivated to practice law by the pursuit of justice or their personal vocation. I will not speculate on the ultimate reason a reader may want to pursue a JD, but our analysis suggests it should not be to make a sound investment.

If you got this far, thanks for reading.

I heavily recommend reading Schlunk’s original paper. While my goal was to reproduce his method with current numbers, it is almost certain I erred in some respect or missed an insightful point hidden in the original. Do give it a look for a more comprehensive understanding of how he went about answering the question.

Also, here is the spreadsheet I used to calculate everything. You can plug in different annual incomes or discount rates to get a feeling for how the results might have turned out otherwise with different assumptions.