In the last post, we described the hypothetical students we are using for this investigation and considered and the type of income they would be missing if they chose to go to law school. Now, we’ll add tuition to the total cost and see how much each would need to earn as lawyers to “break even,” so to speak.

Step 3: tuition and totals

Tuition varies greatly between institutions. In the most egregious of circumstances, you can expect to pay up to $77,000 a year at fancy private law school. Yet, public law schools exist that only charge around $22,000.

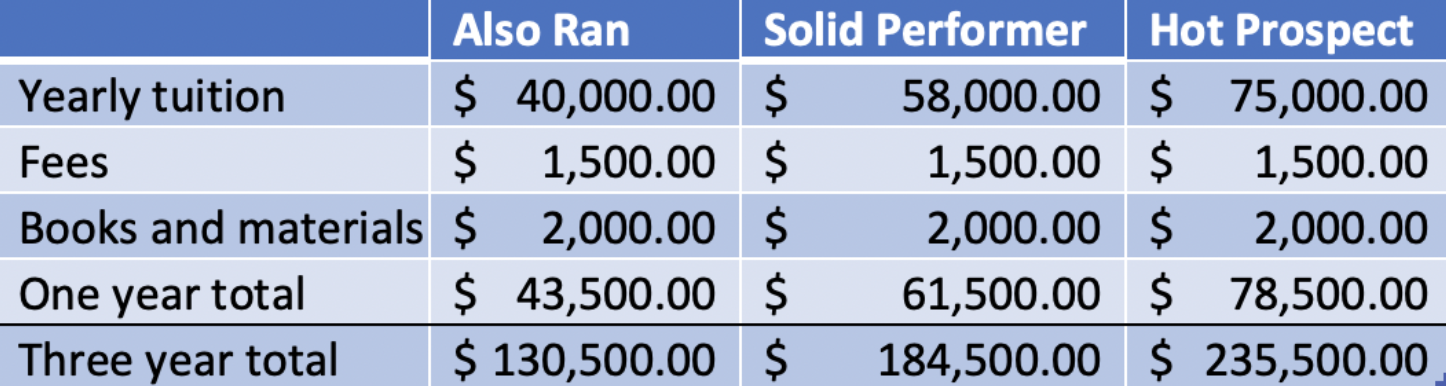

From my amateur research, tuition seems to increase with the prestige of the institution. Accordingly, Also Ran, Solid Performer, and Hot Prospect will probably pay different amounts. To account for the variation, I lifted tuition information from three law schools whose standards correspond to the stated undergraduate performance of our hypothetical students. For Also Ran, a school nearly outside the top 50 in the rankings. For Solid Performer, a school hovering around the 20 mark. Hot Prospect gets the big name T14 law school with the big name prices.

I also added a couple thousand dollars extra to yearly expenses to account for books and university fees.

Table 4

Table 4

These numbers are eye-popping. For context, Let’s assume Solid Performer takes out loans to cover the entirety of her expenses. If she secures a 6.08% interest rate (the federal graduate fixed rate) and makes monthly payments of around $1,500, it would still take her 15 years to pay them off.

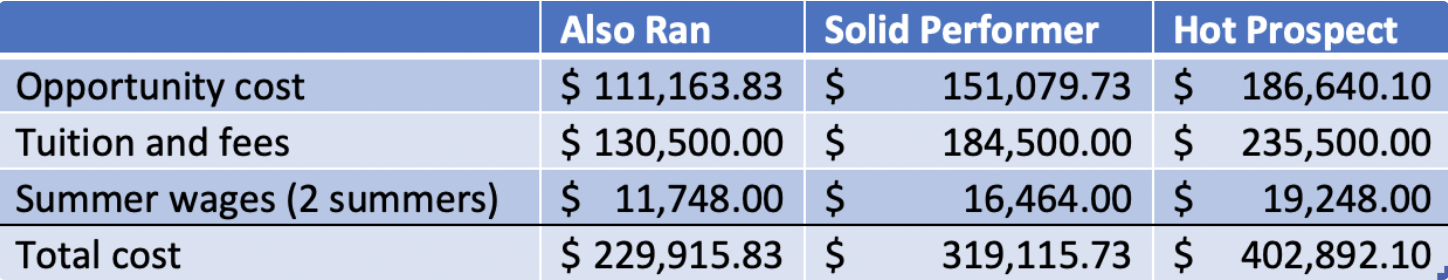

Adding these totals to the opportunity cost figures is truly frightening.

Table 5

Table 5

We’ll soften the blow a bit by taking into account summer employment. Many law students are able to land lucrative summer positions that can lower the net cost of law school. In 2009, Schlunk estimated that Also Ran, Solid Performer, and Hot Prospect can each earn approximately $5,000, $7,500, and $10,000 respectively during a summer.

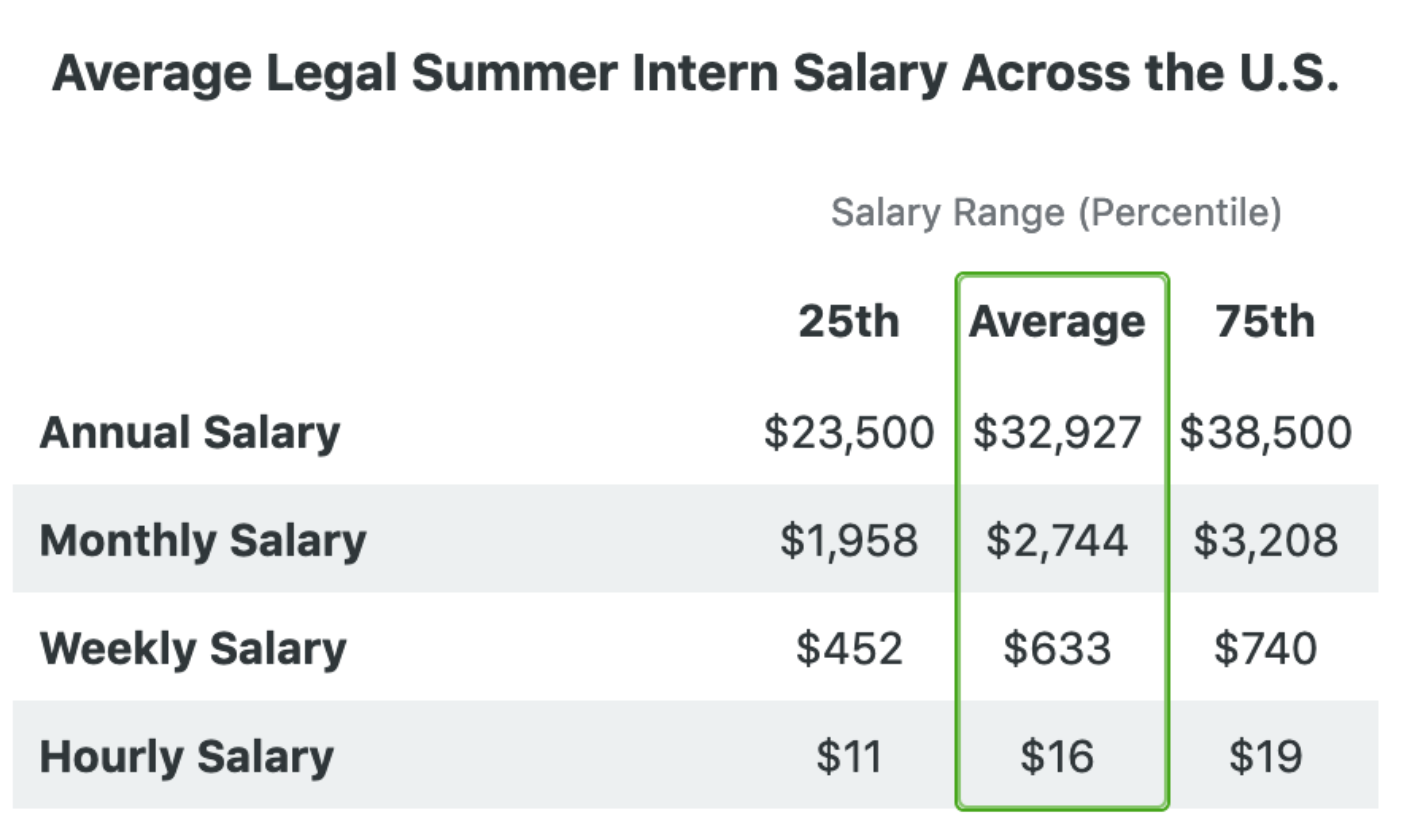

Rather than plug these figures into an inflation calculator, I decided to look for current data. Ziprecruiter has this helpful table on their website.

I think it’s safe to assume Also Ran, Solid Performer, and Hot Prospect have summer earning potentials around the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles, respectively. Subtracting two summers of compensation yields the following total cost figures.

Table 6

Table 6

Roughly, this is how much it costs to go to law school. However, and I hadn’t actually thought about this, there are also significant costs to being a lawyer. We examine those next.

Step 4: hurdle compensation.

If you become a lawyer, it would be nice to earn more than what you would have without a JD. Financially, it would be a disaster if you invested $300,000 and three years of your life to end up with the same earning power as a similar individual who did not go to law school.

As a result, we will attempt to quantify the amount you would need to earn in order to be doing better than your non-lawyer doppelgänger. This is different than just looking at the fourth year hypothetical yearly wages calculated in table 2 of part 1. As mentioned above, actually being a lawyer entails sacrifices that ideally you would be compensated for. Imagine you make $5,000 more annually than your doppelgänger. However, you also have to live in a more expensive city than they do and pay $5,000 more in housing. Effectively, you make as much as the doppelgänger when the additional costs are considered. If you want to “actually” make $5,000 more than your twin in this scenario, you would have to be compensated for the $5,000 you spent in excess of what you would have. Thus, you would have to make $10,000 more than them.

We’ll call this figure we arrive at after adding the additional costs associated with being a lawyer “hurdle compensation.” In our toy example above, the hurdle compensation would have been whatever the non-lawyer doppelgänger had made plus the expenses tied to being a lawyer.

We will consider the cost of housing and overtime pay in calculating hurdle compensation for our hypothetical students.

Lawyers, especially high earning ones, are concentrated in a few American cities. New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Washington D.C. all have ample big-shot lawyer populations and sky-high costs of living. As a result, if one of our students gets a biglaw job, they will most likely have to move to an expensive city.

Lawyers are also notoriously overworked. It’s not uncommon to only bill (charge clients for) 40 hours a week but actually work 60 or 70 hours at large law firms. Our budding lawyers should be compensated for this overtime if they so happen to get a biglaw job.

As with state taxes, I’m not even going to try and figure out an exact cost of living premium owing to the variation across cities. Schlunk assumes an additional 10% of total income is an accurate premium, so I’m going to go with that.

Getting overtime premiums involves less hand-waving and more calculation. We’ll assume the average worker puts in 2,000 hours a year (40-hour weeks), and any hours over this are overtime. We’ll also stipulate that any lawyer has to put in 200 more hours a year than average. Thus, a regular lawyer works 2,200 hours a year.

Now, it’s not unreasonable to assume that while an average lawyer is expected to work 2,200 hours, biglaw lawyers work 2,400 (46-hour weeks).

The going overtime rate is 1.5x your average hourly rate. However, each additional overtime hour is more valuable as it is taken from an ever-decreasing pool of your free time. Thus, Schlunk, and I, assume the first 200 overtime hours should be valued at 1.5x one’s average hourly rate, but the next 200 should be 2x.

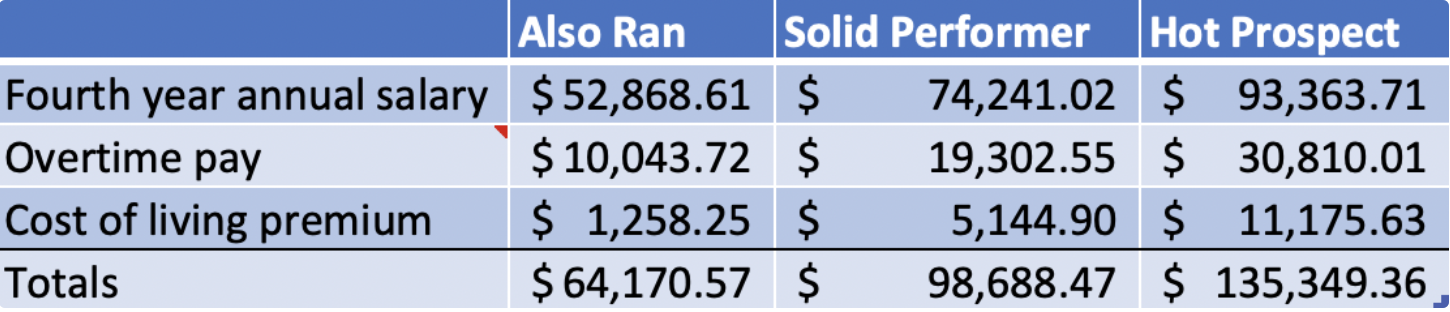

Based on our assumptions about the probability of each student getting a biglaw job, Also Ran will need the cost of living premium and 400 hours of overtime pay 20% of the time, Solid Performer 55% of the time, and Hot Prospect 90% of the time.

Here are the totals:

Table 7

Table 7

As we can see, our three students must make more than approximately $64,000, $99,000, and $135,000 respectively in order to “do better” than their non-lawyer counterparts.

However, these figures do not tell the entire story. In the next part, we’ll consider discount rates and conclude whether the JD was a good investment.