Like many in unmarketable majors, I’ve briefly toyed with the idea of becoming a lawyer. Not necessarily because I have a deep interest in the law, but because going to law school is the ultimate vindication for your humanities degree.

My personal interest passed quickly, but curiosity lingered about the profession. Why do people become lawyers? Is it really as miserable as I’ve heard? Is it even a sound financial decision?

Thankfully, someone has already answered the last question. I recently came across a paper from law professor Herwig Schlunk on whether going to law school is a good investment (spoiler alert — it isn’t).

The paper is a little outdated, being written in 2009, but I wanted to try and reproduce his analysis as best I can with current figures to see if the conclusions change. This post is the first in a series where I do just that. I’ll be following his steps as closely as possible, but will not be comparing my end results to his.

Note that Schlunk, and this series of posts, is attempting to answer the question of “should I go to law school?” from a purely financial perspective. Money aside, people might attend because they feel they could be good lawyers, or they want to contribute to a more just society. Non-monetary reasons are certainly valid, even applauded, but the costs of any type of graduate school should be considered before a prospective student writes the check or takes out the loan. Schlunk acknowledges that becoming a lawyer confers numerous benefits beyond increased earning power, but as he puts it, “you can’t eat prestige.”

Step 1: the students

Because the answer to any major life decision is highly particularized, it’s foolish to perform one set of calculations trying to settle the matter and claim the results apply to everyone. In an attempt to be less foolish, Schlunk stipulates three hypothetical undergraduates with different backgrounds and considers their situations in parallel. (Note: I’m borrowing Schlunk’s names for the students out of convenience).

Let’s meet them.

Also Ran is an undergraduate at a middle-of-the-pack university. He achieves above average grades in a relatively nonmarketable major and could have earned $47,000 in a non-legal job after graduation. He, by Schlunk’s account, “claws his way” into a second/third tier law school and has about a 20% chance of getting a lucrative “biglaw” job after graduation.

Solid performer went to a better college and made good grades in a more marketable major (think economics vs English). He makes his way into a mid tier law school but could have earned $66,000 had he chose to jump into the workforce. As a JD, he has a 55% chance of getting a cushy biglaw job.

Last, we have Hot Prospect. She is the most conventionally successful of the bunch, having a stellar academic record in a marketable major (CS/math/engineering) at an elite undergraduate institution. She gets into another elite university for law school but could have made $83,000 in her first year out of undergrad. However, biglaw jobs aren’t a certainty for anyone, including her. She has a 90% chance of getting one after law school.

Step 2: opportunity cost

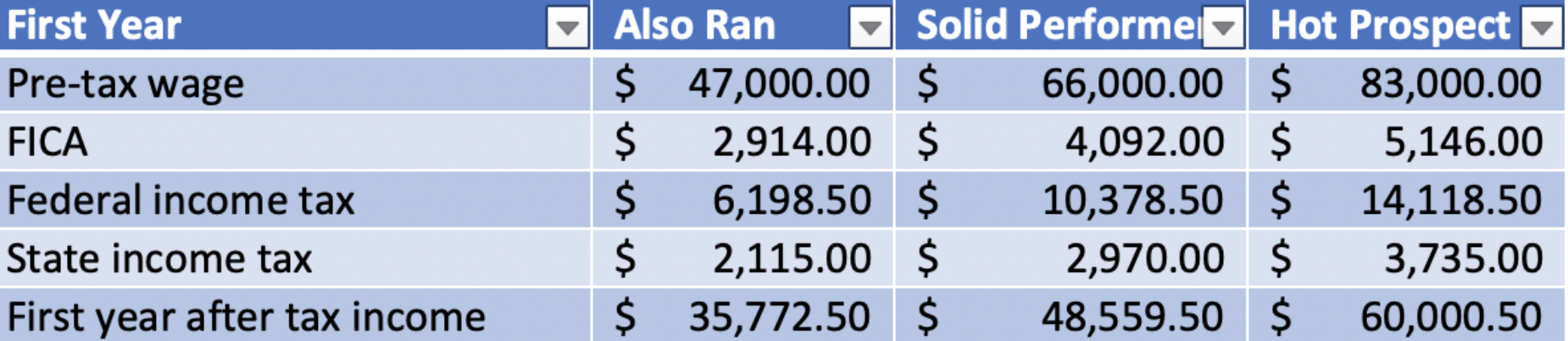

If someone decides to go to law school, or pursue any other type of post-graduate education, they are missing out on potential wages. Of course, not all of what you make goes straight into your pocket. In the table below, I subtract various taxes from the salaries each student could have made in their first year of employment. The FICA tax rate I used was 6.2%, and all three students happened to fall in the same Federal income tax bracket given their first year salaries.

State taxes are trickier as schemes vary wildly across the nation. States like Minnesota and California have a multi-tiered system with differing marginal tax rates. Others, like Massachusetts and Utah, have a single rate for all income. To further complicate things, Texas, Nevada, Washington, and Florida have no state income tax at all.

To simplify my calculations, I’ll make a move similar to what Schlunk did and assume a flat 4.5% state tax rate. This might significantly over or understate the amount of taxes you would pay in most states, but it’s an accurate figure if you’re living in Illionois, for example, with a 4.95% flat rate.

Table 1

Table 1

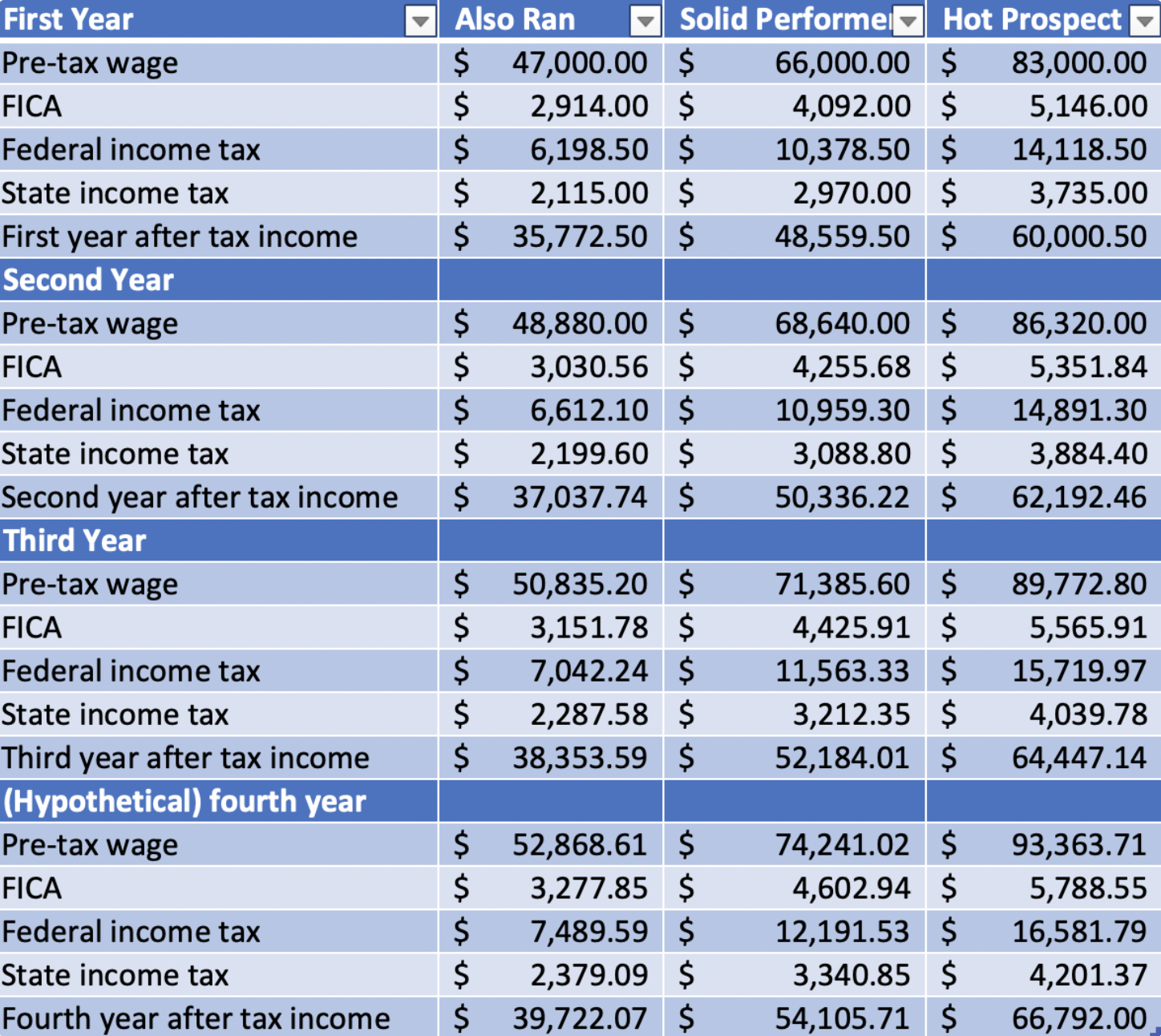

Based on the assumptions above, this is the opportunity cost for each student of going to law school for a single year. Note that it typically takes three years of schooling to get the degree. I could multiply each figure by three, but that wouldn’t account for raises in pay commensurate with increases in productivity. In his calculations, Schlunk accounts for this by bumping pay 3.5% a year but acknowledges this figure might be too low. I assumed a 4% growth in yearly wages and ran the numbers again.

Table 2

Table 2

The hypothetical fourth year is included to illustrate what kind of earnings a potential JD could expect her fourth year post-undergrad had she joined the workforce instead of going to law school. Later, we will compare it to what she would likely earn as a freshly-minted lawyer.

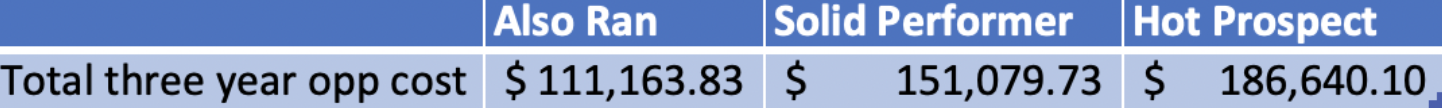

Now, the (rough) financial opportunity cost can be obtained by summing the first, second, and third year after tax incomes.

Table 3

Table 3

Already, law school isn’t looking good. The financial benefits must be large in order to justify passing on $110,000-$185,000. Unfortunately, this is only the opportunity cost. In the next part we will consider the greatest explicit expense to getting a JD.